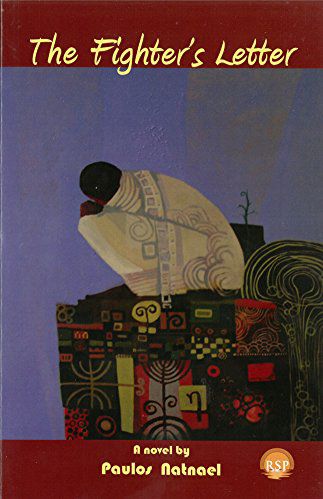

Book Review: The Fighter’s Letter, a novel by Paulos Natnael

The Fighter’s Letter, a novel by Paulos Natnael, is a radical book based on factual story about the Eritrean Revolution for national independence.

The Fighter’s Letter, a novel by Paulos Natnael, is a radical book based on factual story about the Eritrean Revolution for national independence.

Publisher: Africa World Press & Red Sea Press - Trenton, NJ, USA

Publication year: 2015

ISBN: 978-1-56902-410-2 (HB), 978-1-56902-411-9 (PB)

Number of pages: 289

The novel deals with the mammoth task of the struggle for independence and its ups and downs, especially the impeding infightings between the two liberation fronts, the ELF and EPLF.

I have had the opportunity to know Paulos Natnael in the 1990s during my tough years in Dehai, when I had been facing criticism from all sides in the cyberspace, because I used to voice my reservations at the nascent regime in Eritrea. Paulos was one of the few courageous Eritreans who spoke out frankly, which was not easy to do in those years. It carried a huge risk from being ostracized to being threatened. The whole body of Eritrean cyber-intelligentsia and “good-wishers of the government” were fox hunting anyone, who aired anti regime views.

In my view, Paulos’ book, The Fighter’s Letter was prepared with unparalleled openness. The author did not cover up, neither did he exaggerate nor glorify situations and events. This mainly makes the book a unique one of its kind. Another aspect to like about this book is that it encompasses stories of Eritreans from all socioeconomic backgrounds, including the average person. It does not address specific elites or scholars, while excluding others. This too to me showed a great deal of respect for the true makeup of the Eritrean society.

I bought “The Fighter’s Letter” at Amazon Deutschland; it is also available at Amazon UK, Italy, France, and elsewhere. The book can also be purchased from the publisher: Africa World Press & Red Sea Press.

As I read “The Fighter’s Letter”, I was so fascinated by it that I could not put the novel aside. I could not escape the fact that the stories in the novel represented the trials and tribulations of Eritrean families in the 70s and 80s. It shows how members of the same family met different fates through circumstances during that time. As an Eritrean, the stories are bound to captivate you as it did me, as they are, one way or another, intimately close to the stories of most Eritrean families.

The characters in “The Fighter’s Letter” are predominantly an extended family of a certain ato Ysaq. Daniel, one of the grandsons of ato Ysaq and the principal character in the novel, was caught amid the upheavals of the Eritrean revolution’s war. He came from a middle-class family by Eritrean standards. Daniel’s father, ato Haileab, was a self-taught gentleman, who, besides Tigrinya, could speak some other languages: he could read and understand Italian, Arabic, and to some extent Amharic. Ato Gebreab was a strict father, who wanted that all his children have good education. Ato Gebreab always remembered how he and his generation were being deterred by colonial Italy to attend schools beyond the 4th grade. Stefanos, another grandson of ato Ysaq and a role model for Daniel, made it all the way to the USA to attend higher education. The whole family of ato Ysaq was a forerunner family, thriving with hope and success; and Stefanos and Daniel were two bright offspring, innocently pursuing their school duties. The family yearningly refers to its village roots and traditions and at the same time exploits the amenities a modern city can offer. As a matter of fact, this family could be any flourishing Eritrean family and Stefanos or Daniel could be any Eritrean city-kids of that age and at that time. May be that is why deep-rooted Eritreans of that generation could relate themselves with the whole novel.

The book starts with Stefanos Gebreab Ysaq, an aspiring young man, his whole life in front of him, getting ready for matriculation to secure a chance for a higher education. Then the story proceeded to the revolution and its impacts on this certain Eritrean family. Stefanos was very brilliant. He passed matric with honors and went from Asmara to Addis Ababa University, where after his first year he received scholarship to go to a university in the United States. Accordingly, in August 1971, Stefanos left Addis Abba for Buffalo, New York. This was a year or so before the nostalgia of the revolution overshadowed the Eritrean highland and the main towns in particular.

Stefanos’ scholarship was a lucky strike as obtaining university level education with one’s own means was very rare at the economic level of Eritrea at that time. Wealthy families that send their kids for schools abroad were far and in between. For most Eritreans, this was a time when one was considered rich if one’s parents could provide one with food to eat. Many were even worse off than this. As such, kids started working to help their families make ends meet. To have a chance at a university level or at any level for that matter one had to excel in school and work hard.

In any case, Stefanos’ departure for Addis Ababa was very sad for Daniel, as he loved his cousin, Stefanos. Stefanos was not only a cousin to Daniel but also his role model. Daniel admired Stefanos and wanted to be in-all-ways like him. However, that was not to be. Young Daniel was caught in politics. This was how the fate of the two was sealed. Daniel could have been Stefanos and Stefanos vice versa.

Despite the opportunities availed to Stefanos, worries of Eritrea, the state of his family, and the added challenges that come with living in a foreign land accompanied his life. Therefore, at the end, Stefanos too was not able to escape the struggle. The difference is that Stefanos was neither completely here nor completely there. Daniels’s position probably was easier as he has already given his life to the cause of his country; Daniel’s main concern was to make heroic deeds for his country before martyrdom. Stefanos’ life on the other hand was not as cut and dry; he had to fit in, earn a living, study and survive in a foreign land all alone. Therefore, as any Eritrean in exile at the time, he could not help but anxiously suffer from what could be happening to his family and Eritrea as a whole, whether his sibling fighters would make it alive and whether he would see them. Not being able to help them financially was also a struggle in itself. Regretfully, Stefanos ultimately ended up killing himself, perhaps because these successes did not give him the serenity he was looking for.

Daniel has now grown into a young man and he was being called by an idea that was born long ago. An idea was born and this idea banged on people’s ears like a gigantic bell. Eritreans started organizing themselves around the idea. The Eritrean Liberation Struggle was born. It took an armed turn after Hamid Idris Awate fired the first shot against the presence of Ethiopian government forces in Eritrea. This took place in 1 September, 1961 at Mount Adal. The birth of the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) was heralded. After 7/8 years of its inception, the ELF was suffering from internal strife and another Eritrean front, PLF was born. Both fronts, ELF and PLF were at armed confrontations from the very inception of PLF.

After years of infighting on the Eritrean lowlands, the two fronts ascended onto the Eritrean highlands towards the first half of the 70s. They were looking for new recruits and sphere of influence among Eritreans, especially in and around the capital city, Asmara. The two Eritrean fronts were fighting against one another and simultaneously waging war against the Ethiopian colonial army in Eritrea. By 1974 Emperor Haile-Selassie of Ethiopia was ousted in a coup and there were a stalemate between the Ethiopian army and the Eritrean fronts subsequently. This gave the Eritrean citizens, especially those from the cities some respite, providing them with a chance to make pressure on the Eritrean fronts to stop the infighting and to do away with the colonial presence jointly. Hundreds of civilians used to go to Weki-Zager, the two adjacent villages where both fronts were posted facing each other at a range of less than 10 km.

It was at that time the youngsters, Daniel Haileab Ysaq and his four friends, Senay Kidane, Mebrahtu Haile, Simon Seyoum, and Amanuel Stefanos from the capital city Asmara went to Weki-Zager to see the freedom fighters. Asmara kids by the 70s had plenty of access to information about the revolution from, among other sources, leaflets distributed by the liberation movements. It was not strange for teens to be involved in conversations about the revolution, about who from the neighborhood had left and joined the field and in which one of the fronts one had joined. Although Eritreans were saddened and confused by the civil war, young Eritreans still joined the fronts. The civil war was apparently less severe compared to Ethiopia’s havoc on the territory.

By 1975 Ethiopian fighter jets were bombing villages to ashes, the Tor-Serawit (Ethiopian army) used to set fire onto villages at random and bodies of dozens of young Eritreans were found strangled night after night in Asmara. At one juncture, the military junta that replaced Emperor-Haile-Selassie ordered to shoot all Eritreans who attempted to enter the capital from the northern frontier, i.e. from the direction of Weki-Zager. Luckily, Eritrean high ranking officials within the Ethiopian Army, particularly General Aman Andom, who was then heading the Ethiopian Military Junta (Derg) and who paid with his life as a result, interfered.

By the last quarter of 1974, the pressure from the public and the necessity to win the public made the fronts reach a cease-fire agreement, but continued to fight the Ethiopian colonial army separately. Subsequently, each front was joined by tens of thousands of young Eritreans by the end of 1974 and beginning of 1975. Out of the group, Simon and Senay had left by December 1974 to join PLF, the organization that would later rename itself to EPLF. Daniel was also frequenting visits to villages toward the West of Asmara, the area where ELF units were widespread. Every morning Daniel and his remaining friends would check with each other to find out whether someone had left the night before. The city kids were restless because the Derg was hunting the youth arbitrarily. Daniel used to visit the ELF dominions now with another new group, Tesfaldet, Rezene, and Haile. During one of their visits, the new group aired its wish to join the ELF as fighters. Daniel and Tesfaldet were straightaway told to come back prepared, while the other two were told to remain with their parents and try again after a year. In December of 1974, both Daniel and Tesfaldet came back prepared as they were told, finally arriving at Adi-Teklay, where they found an ELF platoon. They were joined by other 25 or 30 recruits and all were taken southwards past the villages of Himbrti and Adi-Gebray towards Bambqo, a village in the district of Sefa´ in Seraye province. Bambqo was at that time a regional headquarter of the ELF, and a military training center was located at a nearby village called Hret-Una. In Hret-Una, the neophytes from Adi-Teklay found yet another hundreds of new recruits. Young people were flocking out from the cities and surrounding villages to join the Liberation Fronts. Obviously, both Fronts in those years were overwhelmed by the new recruits as their numbers soared by ten to fifteen folds of the previous fighters.

At the beginning of 1975, the Derg had begun to invigorate itself with a plan to keep the Eritrean fronts far-off from the cities and the Eritrean highland. A fierce war broke in and around Asmara as a result. The Derg-Regime had a scorched earth at any rate policy in Eritrea, burning and bombing villages and villagers alike. Thus, the fronts were pushed away and had to take the new recruits as far away as possible. The ELF took its new recruits to a training camp called Rbda, approximately 35 km northeast of the Sudanese border city of Kassala, or 15-20 km north-west of today’s “SAWA Defence Training Center” of the PFDJ. The ELF alone had over 10.000 new trainees at the Rbda-Training-Camp by February 1975. A lot of villages were burnt to ashes, which further escalated the anger of the Eritrean civilians at the Derg-Regime and further reinforced the resolve of the youth to continue to join the Liberation Fronts.

By May 1975, the ELF successfully concluded its organization’s Second National Congress. Daniel and his fellow trainees were supposed to have been assigned to the regular army units of the ELA months prior to that date, but were delayed by two or three months due to a delay of the said congress. The delay had to do with a debate of whether the new trainees participate in the congress or not. The congress was not that important to Daniel and many other newcomers at the training camps. For them, it was more important to go out of the training camps and participate in wars against the enemy upon the completion of their training. By June of that year, the long awaited dispatching came and Daniel was at last assigned to a company-unit led by Ibrahim Qutub. The company was positioned northeast of AQurdet in Barka laElay (upper Barka region). In Bark laElay Daniel was afflicted with malaria and rheumatism ailments that he had to go to Debre-Sala clinic and eventually Kassala hospital for treatments. The fatigue and lack of proper diet compounded with the ailments he was subjected to make his treatments and quick recovery difficult. But later on with changes of diet and some rest in the Sudanese hospital of Kassala, his health situation improved rapidly.

In the Kassala hospital, the fighter-patients were planning some sort of strike and Daniel became a witness of a mutiny of his co-patients. The questions and bitterness of the rioters were not directed at the hospital or the Sudanese but rather at the ELF leadership. Members of the executive committee of the ELF came and addressed the questions of the rioting fighters, but the latter would not concede. During the following days, everyone, including Daniel, were evicted by the Sudanese police and thrown out at the border to Eritrea. Daniel was very angry at such a blind measure, especially so as the measure taken was ascribed to Abdella Idris Mohammed, the head of the military office in the ELF. Abdella was the strongest man in the ELF then and he was hostile to the new fighters, particularly those from the highland of Eritrea. The protestors and other patients the protesters won to their side, anew, went back to the hospital on foot, but Daniel with some others continued heading towards Eritrea and eventually joined their respective units.

Anyway, Daniel was glad that he was healthy again and back into his company. His company was ordered to move towards Senhit as a replacement for battalion 262, which was very much reduced in number due to its adherence to the “Fallul” movement. Thus, Ibrahim Qutub’s company or the company in which Daniel was would cover the position battalion 262 used to take care of. In December 1976, Ibrahim Qutub’s company participated in the battle of Genfelom-Tsebab. The battle has already been raging for a few weeks when their company arrived. On the Keren-Afabet road, ELF units covered the western trenches to the east of the Ethiopian Army, while EPLF units were positioned on the northern and eastern flanks of that highway. Both fronts had entrenched themselves in burrows, hiding themselves from Ethiopian fighter planes. Ethiopian forces were trying to pass to Afabet or beyond and both ELF and EPLF were jointly fighting them back. During this battle, Ethiopian fighter planes, usually US-F5s or French-mirages bombarded the positions of both Liberation Fronts nonstop. The fighters would lay low and wait, covering themselves up and anything that reflected sunlight. The machine-gunners of the Fronts would shoot, whenever the planes flew low enough. During one of such raids and while Daniel was on duty guarding atop the high hill, where his platoon was entrenched, a couple of fighter planes came and started hovering above the trenches. ELF machine gunners started shooting at the planes and lo and behold, one of the planes was shot down. Daniel saw as the pilot left his fighter plane and disappeared down the hills to the planes below, where the plane also crashed. The site lay between the position of the Ethiopian soldiers and that of the ELF, directly in front of Daniel’s company. The Ethiopians were throwing at the hills with whatever they had at hand, apparently to keep the ELF fighters in their trenches and in the meantime rescue their pilot.

The ELF fighters congratulated the machine gunners and they triumphantly enjoyed the event. The EPLF fighters were also happy, and through the regular radio communication congratulated the ELF fighters for shooting the fighter plane down. Thereof a team from both sides was sent out to investigate the case. The team came back and conformed that the plane was indeed shot down. On the next day though, the EPLF fighters reversed their testimony as usual; they claimed that the EPLF units were the ones who shot down the Ethiopian fighter plane. This was both strange and shocking to Daniel and his fellow friends, who were near EPLF units for the first time. But his delight could not be obscured by such reversals and twists. The Ethiopian military convoy including hundreds of vehicles and tanks were ultimately forced to withdraw back to the city of Keren.

For years, the issue of uniting both fronts was weighing heavy, especially on the ELF fighters. After years of on and off clashes and the civil war of the early and mid-1970s, the fronts had finally agreed to unite their ranks and files and have One National Democratic Organization in Eritrea. The twentieth of October 1977 was thus commemorated as a historical day for the majority of Eritreans and as the fulfillment of a prerequisite for Eritrea’s independence. Esra Tqmti, the Tigrinya equivalent for the twentieth of October was a culmination of a series of meetings, in which high delegates of both fronts met: the first meeting took place in April 20, 1977 in Damascus, Syria; the second meeting in 21-23 April in Zagher, Hamasien; and the third meeting in June of that year in Hawashayit, Barka. In fact and after all that, only the ELF was willing to form One National Democratic Organization in Eritrea. For the EPLF, the whole exercise was, apparently a political ploy to gain time and hit back when it sees it appropriate for its parochial intentions. While the agreement of Esra Tqmti was in full swing in the ELF, the EPLF was busy provoking the ELF, inter-alia, assassinating many prominent cadres of the organization.

Prior to Esra Tqmti almost the whole Eritrea was under the control of one or the other front. In the year 1977 alone the ELF liberated many provincial capital cities, like Tessenai, Aggordat and Mandefera, while the EPLF did likewise in Keren, Decamare and Naqiffa. This compounded with the agreement of Esra Tqmti, caused awful troubles at the Dergue-Quarters. And in early 1978, the Dergue prepared massive all-round offensive towards Eritrea. Ethiopia was victorious over Somalia in the Ogaden war, and this victory boosted its hitherto dwindling morale. Besides, the Dergue received at the moment huge military support from its new supporter, the Soviet Union. Armed to the teeth with Soviet weapons, tanks and MIGs, Ethiopia sent anew hundreds of thousands of soldiers to Eritrea through three main fronts: the Zalanbessa-AdiQeyh route in Akele-Guzai province, the Mereb-Mandefera route in Seraye province, and the Humera-OmHajer route in Gash-Setit. It was the ELF alone that took the confrontations in all three strategic fronts and was finally pushed back after many months of shattering battles with the enemy. The EPLF was not only unresponsive to those offensives, but was also ridiculing ELF’s attempts at deterring the enemy while still at the Ethio-Eritrea borders. The EPLF could not stop the invasion from the cities and towns under its control and darted off to the Sahel Mountains, yet bragging and boasting about it as a strategic withdrawal.

After retreating deeper inside the countryside, the ELF began reorganizing and upgrading its forces into brigades. So it formed the following 8 brigades: Brigade NO 61, 64, 69, 71, 72, 77, 97 and the mechanized brigade NO 44. Daniel was assigned to brigade NO 97 and this time around was selected for training as a military intelligence officer. In early November Daniel with a few other colleagues travelled to Hawashait, head office and training center of the security department of the ELF, for participation in an intelligence course. His course comprised of both the basics of military intelligence as well as political theory. There he was taught how to collect and retain essential information, how to use radio and other communication equipment including sophisticated miniature camera. He was further taught how to prepare maps of terrains showing relevant positions of military units. In January 1979 Daniel went back to his brigade which was now assigned to the Sahel region, near Arag. Arag had been taken by force from ELF units that were camping there by the retreating EPLF during its so-called “strategic retreat”, which included the whole rear camp of the organization: hospitals and their patient population including the wounded, food supply, fuel services as well as weapons and ammunitions. And the ELF had sent Daniel’s brigade and other units from the mechanized brigade NO 44 to take back the seized location. A few tense weeks later, however, the two organizations agreed to stop the shootings. The ELF for no apparent reason conceded a large area of northern Sahel to the EPLF. The ELF not only left one of its rear positions voluntarily, but it also gave the EPLF two of its brigades, the 97th and the 44th , to join EPLF forces in the defense of the rear area laying from Eila tsaEda to Qarura. The two brigades of the ELF stayed there, fighting along with the EPLF, for 18 long months, although the EPLF later attempted, maliciously and as usual, to depreciate the key role played by the ELF-units.

During 1979, several efforts were made to bring the ELF and EPLF towards the ever elusive unity, but to no avail. In January 1980, a joint counter strike against the Ethiopian forces in Sahel was planned. The two brigades of the ELF along with the EPLF forces in the area worked closer together than ever before and even began exchanging night-secrets (misTir leyti) for the sake of smooth common operations. There was hope to push back the Ethiopian forces back to the plains towards the Red Sea from the foot of the mountains that they then occupied. Unfortunately, the EPLF for reasons only known to them, but could certainly be seen as only cold and selfish, failed to do their part as was agreed upon. The agreement was for both fronts to hit the enemy simultaneously at 6 a.m. All ELF positions, three battalion positions in all, started the attack at the scheduled time. EPLF’s betrayal of the agreement resulted in ELF units taking fire from the right flank where enemy forces were supposed to have been neutralized by the EPLF. Despite the mine-infested fields and all kinds of incoming fire from the right side, EPLF side, Daniel’s battalion managed to overrun enemy positions and capture its trenches. At around 7 a.m., realizing what ELF forces had accomplished, the EPLF moved forward alongside the ELF forces and finally started shooting at the Ethiopians and helped push the Ethiopian army towards the Red Sea. The attack devastated the enemy and the ELF managed to push it into the plains away from the mountains once again. The success was mired by the duplicity and intrigue of the EPLF. They took, by force, captured Dergue military vehicles from a group of ELF fighters guarding captured equipment near Eila Tseda. The ELF, lest another civil war ensue, let that one pass as well. This and many other similar roguish encounters made the hope of unity or even that of cooperation vanish into the thin air.

Eventually, in July 1980, the tension exploded in the plains of AdobHa in the western Sahel region. The first battalion of brigade 97 of the ELA - which was in a defensive position in the surrounding hills – heard and saw approaching light tanks and armored vehicles of EPLF, hiding and maneuvering to pounce onto the said ELF unit. A bitter internecine war, which was fought for a whole year subsequently, and that took the lives of thousands of freedom fighters from both sides (and many more from the Tigray Peoples Liberation Front, TPLF, which had joined the fighting on the side of the EPLF) had begun. A few days prior to this incident, EPLF forces attacked also ELF forces from the 44th brigade, which were scattered about in smaller units in several bases in the AdobHa region. The sporadic and cowardice assassinations of ELF-cadres by the EPLF were now elevated to provoking sizable army units of the ELF. The full-fledged civil war put the Eritrean countryside in flames, and war broke from the tip of Dankalia in the southeast to the Sudanese border in the west and northwest of Eritrea. Even days after the ELF forces abandoned the contested area and withdrew towards Zara, a river that convergence with the Anseba-river further west, the EPLF continued tracking the ELF units and wouldn’t stop the war. The ELF units withdrew further, while still attempting to fire back and defend themselves. Meanwhile the war reached at western Barka, not far from Kerkebet.

Several months afterwards Daniel’s brigade was reassigned to Seraye, one of the provinces in the highland of Eritrea. By early April 1981, his company camped at Hatsina, a village near Areza (Seraye). The company was assigned there to guard the area around the road including the districts of Anagir and Maraguz. Many ELF units had been evacuated from the Red Sea coastal areas and the Denkalia region into the highland province of Akele Guzay afer being attacked by the EPLF. The TPLF had also by then joined the EPLF in the attack against ELF. The TPLF was attacking especially around the 1000km common border areas of Eritrea and Ethiopia.

Daniel’s battalion was ordered to move eastwards to support ELF forces in Qnafna, near the Hazemo plain. At the crossing of the Asmara-Mendefera highway, they encountered an Ethiopian army patrol, but there were only reluctant shots and they could cross that road without considerable hindrance. At arrival in Qnafna, they joined other ELF forces which had been fighting for months against combined forces of the EPLF and the TPLF all the way from Denkalia across Akele Guzay and further to Seraye. And now in the presence of Daniel’s brigade too, a fierce battle ensued until it was cut by nightfall. Nonetheless, the ELF had to pull out is forces, because with the Asmara-Mendefera highway at its back, the Ethiopian army could block them at the rear and they would be sandwiched from all sides. So the ELF forces crossed the Asmara-Mendefera highway and were posted at Adi Bana, Adi Hizbay and the surrounding area in Seraye.

Few weeks later these ELF brigades were ordered to march dawn to Barka towards AQurdet, because the HalHal and Bogu fronts were no longer holding and that the EPLF was pushing deep into the stronghold (Barka) of the ELF. Fierce battles were waged in June 1981 in the SenHit (administration #4) region, and more specifically around Hagaz Awnjeli and Hashela, and in the Barka (administration #3) region, around Seber, Degsay, AQbermenaE, KaElay and Gardeli.

Still, another withdrawal order followed. As the war raged, ELF leadership continued the orders of further withdrawals of its fighters, which made the latter wonder if there would be any merit in holding on at all. Meanwhile, the ELF had lost the Sahel, Denkalia, Akele Guzay and Seraye administrative regions. It had virtually no presence in Hamasien and was now concentrated in the Barka and Gash areas. The rage of the ELA was directed more and more at the leadership, the Executive Committee of ELF, but especially at the military office, holding them responsible for incapacitating the front into losing the war. The Military office was much into retaliating against perceived internal enemy (Melake Tekle etc…) than lead the Eritrean Liberation Army victoriously. It was becoming more and more apparent that the ELF leadership was no longer capable of leading the organization.

At the beginning of August, Abdella Idris, the commander of the ELF forces, came to an area near Sawa and held a meeting with the officers (company leadership and higher) of Daniel’s brigade. Abdella tried to explain that the leadership had some plans to stop the advancing EPLF forces, but nobody would trust him anymore. As it turned out, the Revolutionary Council’s “strategy” Abdella was talking about, was for the ELF to reorganize itself at the border with a plan to fight back and stop the EPLF army at the Sudanese border area. He then sent the brigade to the hills east of Kassala, the Eastern Sudanese city, where the brigade after some time was ordered to surrender the weapons of its fighters to the Sudanese army. The same was the fate of all brigades and fighters of the ELF. Only Abdella Idris, or rather some fighters loyal to him, were allowed to slip away and so evade surrender, and of course with the consent of the Sudan. Those who surrendered their weapons, who were almost all fighters of the organization, were shipped to either of two camps – the Tahday and Korokon camps. While the absolute majority was camped at Tahday and Korokon, Abdella Idris and his followers were at another place called Rasai, far north of the other camps. Abdella’s camp was also in the Sudan, but was exempted from being disarmed by the Sudan, which was revealing that Abdella was part of the conspiracy.

1) On September 29, 1981, a little over a month after the fighters were put at the Korokon camp, a general meeting was held to discuss issues, which were given as discussion points by the EC (Executive Committee of the ELF). The issues varied from organizational unity to rumors of a group that was grooming itself to splinter from the rest and continue an armed struggle. Under this suspicious atmosphere, to carry out and come up with an objective evaluation and common understanding was questionable. In short, a full evaluation of the ELF and its future prospect, if any, was debatable at this point. The RC leadership held its 6th regular session and declared the incumbent executive committee of ELF as incapable and replaced it with a new one. Not even the EC itself would defend itself let alone anyone else shedding any tears at its loss of power. However, now that people are in the Sudan and Abdella and his followers are still armed etc., Abdella’s rivals have lost. Abdella’s main rivals Melake Tekle, Ibrahim Toteel, Tesfamariam Woldemariam, and Abdella Suleiman were removed. Abdella did not want to include his name in the new team; the new EC would not see any light of the day anyway and so also the ELF as an organization. The new arrangement was rejected categorically by the fighters in the Tahday and Korokon camps and the organization was divided into three factions: 1) the Melake Tekle, Ibrahim Toteel, Tesfamariam Woldemariam group 2) Abdella Idris and followers group and 3) the former chairman Ahmed Mohammed Nassir and Ibrahim Mohammed Ali group.

2) After almost a year in the Sudan, the ELF decided to hold an organizational conference to look for a way out of its predicament and Abdella Idris insisted to host the conference. Most fighters objected to the idea of Abdella Idris hosting the conference for obvious reasons: Abdella Idris was armed; the other two blocks were not. Nevertheless, the leadership had stronger argument, the unity of the ELF. The debate at the Tahday and Korokon continued for weeks and finally it was decided that the unity of the ELF was of paramount importance and therefore the Abdella group would get its wish of hosting the conference. Many friends and good wishers tried to dissuade Melake Tekle from participating, but he did not want to be the cause of disunity and therefore participated. On the day the conference was supposed to start, the Abdella group surrounded the site, assassinated the former chief of security, Melake Tekle, and detained most of the participants, including members of the RC. The chances of revival and realignment of ELF, and especially the ELA, i.e. its military wing became sealed after that cowardly assassination of Melake Tekle, who by then was a symbol of hope to renewal within the organization.

Daniel was one of the thousands of ELF fighters, who left the rank and file of the organization and sought a life in the Sudanese cities. By 1987, his application for expatriation was granted and he left for the USA, where he still resides.

In summary, this book is a historical miniature of Eritrean reality that starts in the 70s through a narration of a certain Eritrean family to which anyone of us can relate. In one way or another, any Eritrean will connect to aspects of the stories therein. By implication this book also shows that unlike today, Eritrean life back then was ridden with purposefulness. Regardless of the path taken, one was aiming at and striving for something affirmative. This book is simply a treasure to own!

Freweini Ghebresadick

December 17, 2015

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)