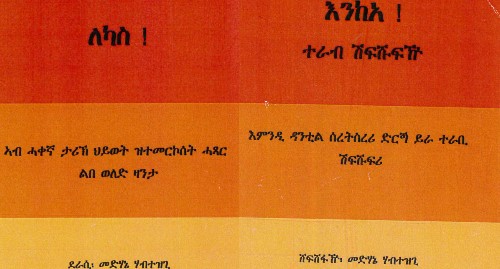

A Brief Book Review: Enkie, (እንከኤ) translated into Tigrigna as lekas (ለካስ, A Surprise!).

Medhanie Habtezghi (2010). Enkie, (እንከኤ) translated into Tigrigna as lekas (ለካስ, A Surprise!). A Novel based on factual events. AITAS e-edit, Oslo, Norway. 132 pages, 12 sections.

A Brief Book Review by Kiflemariam Hamde,

Umeå University,

Sweden

Medhanie’s 2010 book is published both in Blin (እንከኤ) and in Tigrinya (ለካስ). I can translate both as A Surprise! The author dedicates the book to those (1) who find themselves in a bad situation escaping from the atrocities in Eritrea, and (2) those who were jailed, punished unjustly, those who died in search for peace, those whose yearnings for justice never realized, and to those who have lost their voice, the voiceless (Dedication page). The author aims to give voice to the voiceless and the silenced!

This is a brief note rather than an elongated review as readers who understand Blin and/or Tigrinya can have access to either of them. I will thus confine my note to the main storyline. Enkie, (እንከኤ) or (ለካስ, a Surprise!) is the second novel by Medhanie Habtezghi who lives in Oslo, Norway. The first novel that he authored in 2008 was titled as Lexen axra merwedi (A Ring that Inflicted Pain, or literally, The Ring which became a Sore) and the review appeared in Asmarino.com. For the current work, the subtitle tells us that the novel is based on reality for the first 10 years after the Independence of Eritrea in 1991. So, I can guess the events occurring after Independence up to 2010 might be the bases for the story. The main story line deals with the fate of one of the main actors who grew up after Eritrea’s liberation, and narrates what happened to the Eritrean youth since then. The main actor, Zeresenay Andit, lost both his parents in liberating Eritrea. His grandmother lived outside of the capital city and all of her four children joined the liberation war and were martyred. She had to raise Zeresenay after liberation but upbringing him was not either any easy encounter with the vagaries of life. The story could apply to any (typical) Eritrean youth since the 1990s, namely youngsters finding themselves alone, one or both parents dead, growing up during the hysteric early 1990s after the liberation of the country, yearning for full liberation, a free Eritrea, and dreaming of education, prosperity, tranquility, and peace. Alas, holds the author, these expectation turned out to be rather more of a dream than the reality. Expectations and sacrifice never intersect with reality!

Zeresenay grew up hearing a lot about the beauty of Asmara city, especially the down town streets with the Independence Street stretching amongst the city’s main buildings, which signified real freedom. The Street, for Zeresenay, was a symbol of victory even if it was not accessible to his grandparent generations when the Italians created it and called it, in daily parlance, ‘Campushtato’. Even during the British Administration (1940s) that Street was barely allowed for the locals (Eritreans) but to a limited scope. Yet, after Ethiopia annexed Eritrea as part of its entity, the Street changed a name with its new masters and became the arena of domination and rule by foreigner entity. Moreover, it was mainly Europeans who owned the retail shops and entertainment sites until Dergue replaced Emperor Haile-Selassie as new rulers of Ethiopia (1974). With Eritrea’s Independence in 1991, the street was rightly named “Independence Street”, a symbol of freedom and tranquility, thought at least the majority of Eritreans if not all of them. The main actor Zeresenay also yearned to visit it one day, as many Eritrean youth residing outside of the capital city who wished to walk stably along the Independence Street to “show at last freedom prevailed” (page 2) and entertain themselves in their own capital city. Although, one day, Zeresenay travelled and succeeded to come to the down town, to his surprise, he found out that Asmara city was still dominated by people with alien and foreign names who were the same personalities as during the Dergue era (1974-1991). Moreover, once in walking in the Street, Zeresenay experienced the unexpected: he faced enmity and opposition, and was treated as an alien in the very capital city which he thought symbolized liberation and peace. He was eventually captured, jailed and punished by the cruel old Dergue guards who served now the Eritrean government instead of leaving people to live in peace. That was a shock and a Surprise to Zeresenay, and all his dreams were to come to be true later on. ‘Nothing has changed, it became even worse’, pondered Zeresenay as he faced the opposite of what he and everybody else expected after Eritrean Independence. In the jail where old Dergue security personnel still worked (Section 2, pages 16-29) he met and learnt a lot from Eritrean prison mates who were there for no apparent crimes. Some of the inmates served prison three times, first under the Emperor in the 1960s, then under the Dergue since mid-1970s, and now under the Eritrean government, and in all of them, the same security investigators and interrogators served. For example, he remembers two of the security called Amsalu and Akalu (30-31). He was released however, with no reason given!

To make the long story shorter, in the meantime Zeresenay got married to Yordanos, got a baby daughter whom they named Rahwa (Tranquility) to fulfil their wish for a peaceful life. The atrocities that he once encountered as mere dreams came out to be true for many young Eritreans. Consequently, to escape these atrocities, many youngsters were but forced to flee towards the Sudan, experiencing the hazardous life towards that, the ungoverned situation in the Sahara desert, unexpected and arrogant bandits in Libya, and worse enough, the journey toward safety via the Mediterranean Sea. In the last Section of the book (pages 124-132), the author recounts events in the Sea. After many tribulations, the family decided to cross the Mediterranean Sea towards Italy, and on their way, the ship wrecked, leaving 54 dead out of the total 154 travelers. Moreover, their young daughter could not make up the whole route in journey as she dropped off her father’s hands at the chaotic moment. The survivors were taken to Maltese hospital, and not to Italy. Once his grandmother had interpreted his dream of saving his half body from the sea while the other half was drowned. He had thought that was a mere dream. However, in that Maltese hospital, now that he lost his only daughter Rahwa, he realized that the dream was not a mere dream but A Surprise, wherefrom the title of the book derived.

The book was written by the end of the last decade and published in 2010, well before the deadly events in 2013 when almost 350 Eritreans were drowned in Lampedusa. But those stories were not widely spread at that time. That is why the novel is realistic enough so much so that for last few years, the contents of the story have become daily news in the whole world, and instant feelings of guilty and anguish among Eritreans. As in his previous novel, the Ring that Became a Sore, to make his point, Medhanie makes use of many allegorical speech, in both the Blin and the Tigrinya versions, rhetorical and proverbial expressions. In many of the Sections, Medhanie turns to a poetic language. For example, in page 11 in the Blin version, there is a poem on the beauty of Asmara by pro-government supporters, and on page 13 a crazy but realistic guy, Aygdudu, exposes the hypocrite and false promises of the former. For their aesthetic character, both the Blin poem and Tigrinya tend to have been written independently of each other and not translation to either of them. This paradoxical combination of poems and verses shows how emotions and rationality, joy and grief, hate and love, moments of challenge and opportunity can be expressed in different genres, and in one text. The poetic expression even give time for less monotone reading of the paragraphs. In spite of the real but sad stories in the latter work, the reader can still enjoy the beauty in the language. As a reader, I can only appreciate Medhanie’s linguistic competence not only in his mother tongue, Blin, but especially in his mastery of the Tigrinya language. I thus encourage readers of both languages to read this great literary work, which gives vivid life to the lifeless, and greatly provides voice to the voiceless, as the author dedicated to the work for them. He reminds readers about the real but sad challenges Eritrean youth are facing nowadays. I hope the author continues with a third book on the fate of Eritreans once they reached their final destinations (safely).

A much deeper comprehensive review might be required to do justice to the contents of the whole story, especially from the point of view of literary theory and literary criticism. My overall evaluation however, is very positive in the use of complex language in both Blin and Tigrinya, the author’s skills in interspersing prose and verses, idioms and proverbs, and the terminology in Blin to fill gaps in the existing vocabulary.

This book is in fact “a voice to the voiceless and the silenced” modern Eritrean youth who are disappearing and suffering in the hot and cruel sands of the Sahara and Libya. The message is a reminiscent of Abba Gerbreyesus Hailu’s novel, Hade Zanta (1928) when the Italian colonizers had forced our grandfathers to tread those very locations as conscripts. I encourage you to read it in Blin ((እንከኤ) Tigrigna (ለካስ) or both!

Medhanie Habtezghi lives in Oslo, Norway, and is a father of four. He has earned L.LB at the University of Asmara (1999) and wrote the LL.B senior thesis “Customary Marriage and Divorce in Blin Society”. He did his Masterate degree in Public International Law (2010) with a thesis titled “Environmental Protection in Eritrea under the Light of Biodiversity Convention and the Rio Declaration Principles: the Interdependence of political, Economic and Environmental Principles”. University of Oslo, Norway.

Medhanie can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)