Eritrea raising money in Canada, financing terrorists to attack Canada

The government of Eritrea, which the United Nations accuses of supplying a long list of armed groups including the al-Qaeda affiliate Al-Shabab, has been raising money in Canada by taxing Eritrean-Canadians, interviews and documents show.

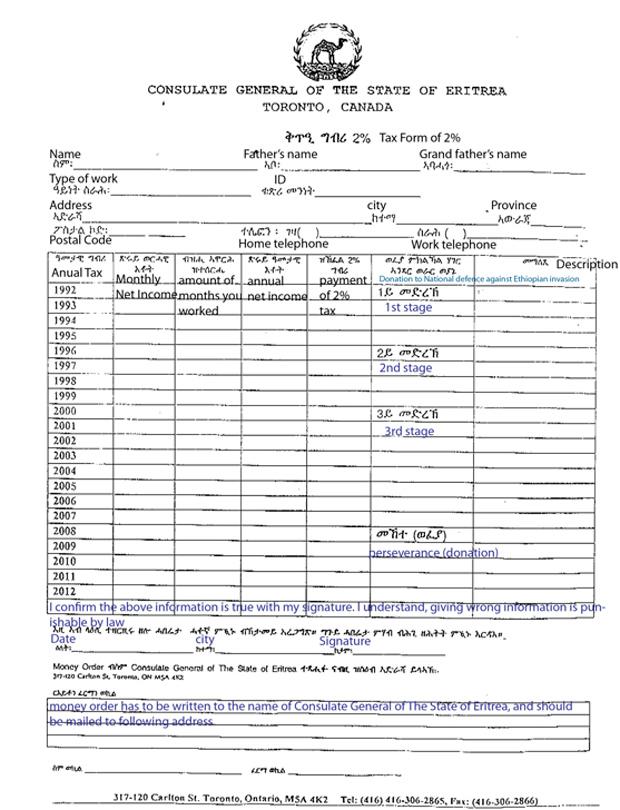

The 2% “diaspora tax” is collected by the Consulate General of Eritrea in Toronto and helps explain how one of the world’s least developed countries raises revenues as it trains, arms and finances rebels from Sudan to Somalia.

In interviews, Eritrean-Canadians told of being pressured to give 2% of their earnings to Eritrean diplomats and agents in Canada. They showed receipts and forms that verify the tax collection scheme is taking place.

“Two per cent tax form,” reads a document on the letterhead of the downtown Toronto consulate. There are spaces on the form for reporting monthly and annual income going back to 1992, the first full year of Eritrea’s independence.

A separate column is labeled “payment of 2% tax” and another is for “donations to national defence against Ethiopian invasion.” The form was obtained from the consulate last week, indicating the collection is still going on.

“That is extortion,” said Aaron Berhane, a journalist who fled Eritrea and now lives in Toronto. He said Eritrea gets about a third of its revenues by milking the diaspora. “They are forced to pay that tax.”

While several countries levy fees on their nationals abroad, Eritrea is unique because it has been widely accused of distributing weapons and money to Al-Shabab — which last weekend released an audiotape by a suicide bomber that called for terrorist attacks in Canada and “anywhere you find kuffar [infidels].”

This week, Eritrea was accused of delivering two planeloads of arms to Al-Shabab. Eritrea denies the allegations but the UN has gathered compelling evidence of the country’s support for the hardline Islamist group.

“In spite of its relative poverty, Eritrea has long acted – and, in the assessment of the Monitoring Group, continues to act — as a patron of armed opposition groups throughout the region, and even beyond,” reads a UN report released in July.

Because of Eritrea’s conduct, the UN imposed an arms embargo on the country in 2009 but the Security Council is now considering a wider range of sanctions to pressure the government of President Isaias Afewerki.

Among the options under consideration is an international ban on the diaspora tax. Canada implemented the UN sanctions last year but the Department of Foreign Affairs would not say whether it supported the latest proposal.

“It is premature to comment on the outcome of discussions on a draft UN Security Council resolution, including any reference to a ban on the collection of a diaspora tax,” said Claude Rochon, a foreign affairs spokeswoman.

She said the department had not received any complaints about the tax but added, “we encourage anyone who may experience this type of intimidation to contact local police authorities and/or the RCMP. Our government stands firmly against terrorist organizations and those who support them.”

Abraha Ghebreslassie, a refugee from Eritrea who now lives in Toronto, supports a UN ban. He called it “absolutely ridiculous” that a country that was aiding Al-Shabab was collecting taxes in Canada. But he said Eritrea’s repression of its own citizens was his main concern. “The Eritrean government is being supported by the Canadian people here, Canadians contributing to oppress my people.”

Eritrea is a tiny African nation of six million on the Red Sea, wedged between Sudan, Ethiopia and Djibouti. It is almost totally lacking a modern economy. The diaspora tax is one of its main sources of income.

Ahmed Iman, a consular officer at the Eritrean consulate in Toronto, said the country was decimated by a 30-year independence war and imposed the “voluntary” tax to pay for reconstruction projects such as roads, schools and hospitals.

He said it was not illegal and denied the extortion allegations, likening the tax to a government service fee that was only levied on Eritrean nationals. Those upset about the tax “want something from the country, at the same time they don’t want to fulfill what the country is asking. It’s impossible,” he said.

But the UN report said those who don’t pay may be denied entry to Eritrea, their property in Eritrea may be seized and their family members may be harassed. Expatriates visiting Eritrea have been denied permission to leave the country on the grounds they have not paid the tax.

The diaspora tax may even violate the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, the UN said. “In locations where Eritrea lacks diplomatic or consular representatives, the tax is often collected informally by party agents or community activists whose activities may, in some jurisdictions, be considered a form of extortion.”

Eritrean-Canadians said they were essentially blacklisted by the government until they paid up. They said they were denied things as simple as getting permission for a family member to access their bank account in Eritrea until they had paid the tax.

Some said tax collectors in Canadian cities will visit Eritreans at home and make note of those who don’t pay. They said failing to pay meant problems for their families in Eritrea, and harassment by government supporters in Canada.

“It is not voluntary,” said Mr. Berhane. He said if it were, few would pay it. Why would refugees, forced to flee Eritrea, willingly give part of their earnings to the government that made them exiles? “To pay to the government that really abused you, your community, your country, that is extortion for sure.”

Mr. Berhane said because it is so dependent on the taxes, the Eritrean government takes them seriously, even asking to see T-4 slips and Revenue Canada forms to prove Eritrean-Canadians are accurately reporting the incomes. “So they can’t call this voluntary, this is totally extortion.”

A quarter of Eritrea’s population, about 1.2 million people, lives abroad and the UN estimates that tens and possibly hundreds of millions are generated by taxing them. The Canadian-Eritrean community is small but growing. Canada granted permanent residence to 744 Eritreans last year, up from 662 in 2009 and 470 in 2009. Canada has accepted more than 500 Eritrean refugees since 2008.

“When we came here we thought we were in a free country where we can say what is right. And we find people here asking us for money and telling us not to say anything against the government,” said a man who asked not to be identified to protect his family in Eritrea.

He said he was a university student in 2001 when the government launched a harsh crackdown on political dissent. He was arrested as a suspected government opponent and beaten until he fled Eritrea and ended up in Winnipeg.

Eager to continue his studies in Canada, he prepared his applications but realized he would need his university transcripts from the Eritrean capital, Asmara. When he asked for them, he was told they would be sent — as soon as he had paid the 2% diaspora tax.

Because he made little money, the tax was only in the hundreds of dollars. But it bothered him to give money to the same regime that had made him a refugee. “It is more than extortion,” he said, adding the UN should pass the resolution.

After the money is collected from the diaspora, it enters what the UN calls “increasingly opaque financial networks.” Much of it appears to go, via transfers and couriers, to Dubai, the financial hub of the ruling Peoples Front for Democracy and Justice party. The U.S. says some also goes, through Malta, to East European arms vendors.

By some estimates, 15,000 Canadians of Eritrean origin live around Toronto. Assuming they earned the average household income, if all paid the diaspora tax that would generate more than $10-million a year.

But some won’t do it.

Mr. Berhane ran a popular newspaper in Asmara until it was shut down by the government in 2001, as part of a broad assault on the press by President Afewerki, a former rebel who has ruled since independence.

Told he was about to be arrested, Mr. Berhane fled his home and walked across the border to Sudan. He now runs an Eritrean newspaper in Toronto and, as a matter of conscience, refuses to pay the diaspora tax.

But there was a price for his resolve: His wife was prevented from leaving Eritrea, he said. She was told if she wanted an exit visa, Mr. Berhane would have to pay the tax. He wouldn’t. She finally arrived in May, 2010.

It took eight years.

(Source: National Post)

{jcomments off}

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)