New revelations about Eiraeiro prison camp

New revelations about Eiraeiro prison camp – “The journalist Seyoum Tsehaye is in cell No. 10 of block A01”

Reporters Without Borders

Press release

30 January 2008

ERITREA

Independent journalist Seyoum Tsehaye, the most recent winner of the Reporters Without Borders - Fondation de France press freedom prize, is still alive and is being held in a secret prison camp called “Eiraeiro,” located near the village of Gahtelay in a mountainous desert region north of the Asmara-Massawa road. Seyoum is in cell No. 10 of block A01, which is reserved for the most sensitive political prisoners.

Reporters Without Borders learned this and other details this month from an Eritrean who has had access to the prison, where many political leaders are held. The source must remain anonymous for his protection.

According to this source, Seyoum was transferred to Eiraeiro in about 2003. He was seen being beaten by guards a year or two after arriving in the camp. Very agitated, with his head shaved and a long beard, he rebelled several times against the guards in charge of him, refusing the prison food and repeating : “I did my duty,” “it is my responsibility” and “I don’t care if I die here.”

Head of public television immediately after independence, Seyoum subsequently went back to being a freelance photographer and filmmaker. He and around 10 newspaper publishers and editors were arrested in the course of a round-up ordered by President Issaias Afeworki and his aides in September 2001 after several leading members of the ruling party (the only one permitted) and the military had publicly called for democratic reforms.

He went missing within the Eritrean prison system in April 2002, when the authorities transferred him and several other prisoners of conscience led by Fessehaye “Joshua” Yohannes to secret locations in order to conceal the hunger strike they had begun with the aim of pressing their demand to be taken before a court.

The Reporters Without Borders source described this high-security prison complex in detail, how it operates and the conditions in which the detainees are held. Some initial information about the camp was published in 2006 in a report compiled by the Ethiopian intelligence services. But it consisted of second-hand information. This report summarizes the information provided by a first-hand witness directly to Reporters Without Borders. It confirms the initial information published about this prison, which is described as “not the worst of Eritrea’s prisons.”

Access

Detainees are blindfolded when they are taken in 4WD vehicles to Eiraeiro, located a few kilometres from the village of Gahtelay in Northern Red Sea province, in a region where the temperature can fluctuate from 40 Celsius by day to several degrees below zero at night. After Filfil, a new road leads into a mountainous area where there used to be a coffee plantation. After about 45 minutes, the road is blocked by an initial checkpoint manned by several guards. No one is let through without a laissez-passer stamped by the president’s office. The guard in charge must telephone the camp administrator and have the vehicle searched before allowing the prisoner and his escort to continue on their way to the place identified as “hill 346” on the military high command’s maps.

Since 2005, the special units in charge of guarding the camp have worn beige camouflage uniforms and caps. Previously they wore the sand-coloured uniform called Milano, which the Eritrean independence fighters used to wear. They are armed with AK-47 assault rifles and clubs. Before taking up the post, they must swear an oath pledging never to reveal anything about Eiraeiro.

Since 2005, the special units in charge of guarding the camp have worn beige camouflage uniforms and caps. Previously they wore the sand-coloured uniform called Milano, which the Eritrean independence fighters used to wear. They are armed with AK-47 assault rifles and clubs. Before taking up the post, they must swear an oath pledging never to reveal anything about Eiraeiro.

About one kilometre after the barrier are the barracks of Eiraeiro’s guards, then the outer perimeter of the camp itself, delineated by barbed wire on this side and by a minefield on the north side of the camp. After this second checkpoint, the prisoners are taken to the administrator’s office in an L-shaped building on the edge of the complex. This building also houses a bakery, a medical post, a pharmacy and a bedroom for senior officials from Asmara such as President Issaias himself.

The prisoners are taken before the camp administrator, Lt. Col. Isaac Araia, also known as “Wedi Hakim.” They and their escorts - and even official visitors who come from Asmara to interrogate a detainee - must empty their pockets and leave behind any pieces of paper or pencils they may have brought with them. The administrator checks the laissez-passer and visit schedule in a room with two surveillance cameras. He makes the prisoners sign a form that identifies them by name and he gives them a uniform consisting of a blue shirt and trousers, together with military blankets and a sleeping mat.

An African gulag

Barefoot, under escort and strictly forbidden to talk to, or even look at, the other detainees or guards they pass on the way, the prisoners enter the camp proper, which is surrounded by a four-metre-high wall and are taken to one of the three buildings that hold the cells.

On a flat area below the administration building, the prison camp is an E-shaped complex of three cement buildings, each containing a total of 64 separate cells separated by thick walls. Each wing is identified by a letter and a number. The three sections holding the most politically sensitive detainees, including the journalists, are A01, B01 and B03.

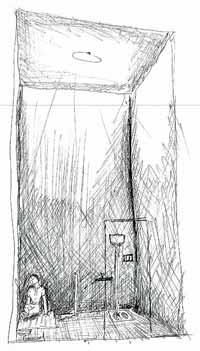

A cell in Eiraeiro seen by an architect

In each wing, a first row on cells gives on to the outside, and a second row gives on to a corridor running through the building. “The blocks were built on the principle that the doors of the cells give on to a wall, so that you cannot see the other detainees,” the Reporters Without Borders source said.

The cells are windowless rooms, 3 metres square, with ceilings high enough to be out of reach, and lit 24 hours a day by a bulb behind an opaque plastic globe. They have a numbered metal door with a 10-centimetre-square spyhole through which the guards give the prisoner his food. Inside the cell, to the right of the door, a hole in the ground serves as a latrine. Above it is a pipe that delivers water but only the camp administrator can turn on the supply.

A one-metre-high metal bar projecting from the floor at the far end of the cell, opposite the door, is used for punishments. If the guards think a prisoner has behaved badly (a look or comment to another prisoner or to a soldier, for example), the prisoner is bound to the bar by the feet and by the hands behind the back, in a squatting position. They are forced to remain like this “for at least 40 hours,” the Reporters Without Borders source said.

The daily hell

The prisoners are kept day and night under the light of an electric bulb and in complete isolation. Some are manacled by the feet or hands. Others are not. When they are not shut up in their cells, the prisoners are taken to one of the three interrogation rooms. The interrogation sessions are often conducted by Abdulla Jaber, the security chief of the ruling People’s Front for Democracy and Justice, or other senior officials such as Yemane “Monkey” Gebread, President Issaias’ advisor. The prisoners are tortured during these sessions. They are hit with plastic whips, for example. There are messages written over the doors of the interrogation rooms. One says : “Did you see who died before you ?” Another says : “If you don’t like the message, kill the messenger.”

The heads of the prisoners are shaved every two months by a barber, who is accompanied by a guard to prevent him talking to them. They are given food twice a day in a plastic bowl - a soup of lentils, vegetables or potatoes. They also have a glass of tea in the morning and six pieces of bead. They are only allowed one litre of water a day. Detainees in very poor health may he given an additional water ration, but only if prescribed by the camp physician, Dr. Haile Mihtsun. If he issues a prescription, it is posted on the cell door. The administrator turns on the water in the pipe over the latrine for only 20 minutes a week. The prisoners have to wash themselves and their clothes in that short period of time.

According to information obtained by Reporters Without Borders in Asmara and abroad in 2006 and 2007, at least nine prisoners had died in Eiraeiro including Tsigenay editor Yusuf Mohamed Ali, believed to have died on 13 June 2006, Keste Debena deputy editor Medhane Haile, believed to have died in February 2006 and Admas editor Said Abdulkader, believed to have died in March 2005. Reporters Without Borders subsequently learned that poet and playwright Fessehaye “Joshua” Yohannes, co-founder of the now banned weekly Setit, died in detention on 11 January 2007. The source interviewed this month confirmed Fessehaye’s death in detention. He said he was held in cell No. 18. He also said there is a cemetery “behind the administrator’s building where at least seven people are buried.”

Recommendations

The prison camp known as Eiraeiro is a disgrace for Eritrea and Africa. The leaders attending the three-day African Union summit that begins on 31 January must not turn a blind eye to the fact that the Eritrean government acts with extraordinary cruelty towards all those it regards as a potential threat to its survival.

In the light of this information, Reporters Without Borders recommends that :

- That the governments of the African Union member states and the leading democratic nations summon the Eritrean ambassador in each of their capitals to express their revulsion at the inhuman treatment of political prisoners and to request their release. The foreign ministries should also demand an end to the extortion practised by Eritrean embassies to supplement Asmara’s finances. All Eritreans living abroad are forced to hand over at least 2 per cent of their income to their embassy in the country where they reside, under pain of being forbidden to return home, own any property in Eritrea or send packages to their families.

- The European Union should adopt targeted sanction against the officials responsible for repression and prison camps. The following persons, in particular, should at the very least be banned from visiting EU countries : presidential chief of staff and spokesman Yemane Gebremeskel ; special presidential adviser Yemane Gebreab, whose presence in Eiraeiro and other camps has been reliably reported ; defence minis ter Gen. Sebhat Ephrem ; camp administrator Isaac “Wedi Hakim” Araia ; local government and information minister Naizghi Kiflu, who was responsible for the 2001 round-ups ; acting information minister Ali Abdu, who is in charge of propaganda ; camp doctor Haile Mihtsun ; Col. Michael Hans, also known as “Wedi Hans,” commander of the 32nd division, which is in charge of the area where Eiraeiro is located ; Col. “Wedi Welela,” head of intelligence in Administrative Zone No. 5 ; and former camp administrator M aj. Gen. Gerezghiher “Wuchu” Andemariam.

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)