Eritrea-Ethiopia: A Confederation We Didn’t Vote On

SOURCE: eritreadigest.com

A confederation is an institutional arrangement in which the policies of different districts are, at least in part, influenced by the preferences of voters from other districts in the confederation. In practice, this is usually accomplished through a complex array of overlapping jurisdictions, representative governments at different levels, and a legal system that allocates decision-making authority and responsibility across these different levels. The end result is ultimately a vectors of policies, one for each district. – Political Confederation Author(s): Jacques Crémer and Thomas R. Palfrey Source: The American Political Science Review, Vol. 93, No. 1 (Mar., 1999), pp. 69-83

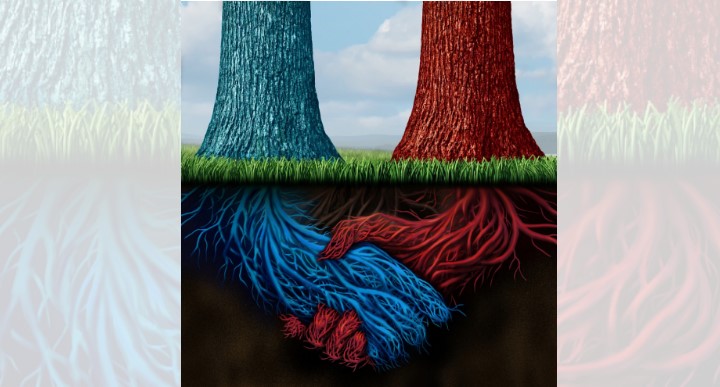

In this article, I argue that Eritrea and Ethiopia are well on their way to forming a confederation. This would be the fourth type of configuration for the two countries. Take One: Eritrea-Ethiopia Federation of 1952. Take Two: Dissolution of Federation and Annexation of 1962. Take Three: Referendum and Independence of 1993. Take Four: the “Peace & Friendship” Agreement of 2018. What’s noteworthy is that, unlike all previous configurations (federation, dissolution, independence), the present one is happening without the vote (even a coerced one), or even the knowledge, of the Eritrean people.

The first thing to say about this is that both the government of Ethiopia and Eritrea (in the person of Isaias Afwerki ONLY) had expressed their desire for this as early as 1993. Shortly after Eritrea’s referendum on independence was held, Reuters reported (on May 3, 1993) that then-President Meles Zenawi “did not rule out confederation, a view shared by Eritrean leader Isayas Afewerki.” The second thing to say about this is that, on the merits, this may very well be the best arrangement for Eritreans and Ethiopians, but that’s hardly the point. The third thing to say about it, which will be the focus of this article, is that the author’s objection to it is that it is being done, at least from the perspective of Eritreans, very secretly and without consulting the people. It appears to be the execution of the long-term dream of President Isaias Afwerki, now that all who may oppose him are dead or disappeared or exiled. The fourth thing to say about it, which we won’t spend a lot of time on, is that confederation arrangements are almost always a stop on the path to fuller integration (federation, union) or separation following dissolution. That is, confederations between sovereign states are almost always temporary because there isn’t a long-term agreement on how weak or strong the “center” ought to be.

In this new configuration, what one notices is an assertive Ethiopia in contrast with a meek Eritrea; a delegation of responsibilities from Eritrea to Ethiopia; an absorption of responsibilities by Ethiopia (from Eritrean state media to Ethiopian media, where Eritreans now go to hear news about Eritrea); rewriting history in a way that is most favorable to the “we are one people” narrative; absolutely no change in the governance of Eritrea and zero reform in its criminal path; two leaders who scorn the involvement of people in decision-making; and lastly, people who knew better, should have spoken up much sooner, now saying, “oh, yes, I saw the warning signs early on.”

Here are the sequence of events:

June 26, 2018: It all started in Addis Abeba. Six days after Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki informed the world that he was sending delegates to Addis Abeba to study the Ethiopian proposal for peace, his two delegates, Foreign Minister Osman Saleh and PFDJ Political Director/Presidential Advisor Yemane Gebreab arrived in Addis Abeba to a stately reception. In his address, Foreign Minister Osman Saleh, referring to the reception, said that he can bear witness that in Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed “we have a humble leader” (ናይ ብሓቂ ምቕሉል ዝኾነ መራሒ ከም ዘለና…)

This was dismissed as a slip of tongue, perhaps from someone to whom Tigrinya is not a first language and is not known for being a great orator. Perhaps the great speaker and polemicist Mr. Yemane Gebreab would say something that reflected the sentiments of Eritreans: a peaceful but proud people? It feels like the last 20 years never happened, he said. Then he used the word “love”, which was such an uncomfortable usage in his parlance he felt compelled to sheepishly credit it to PM Abiye Ahmed.

July 8, 2018: Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed arrives in Asmara, Eritrea. In his address at a State dinner, President Isaias Afwerki, hosting the event, says he has no prepared speech. After describing the elation people showed in welcoming Abiy Ahmed as an ability to exercise their right (how?), he laments the lost opportunities of the past 25 years. Not 20 (since the 1998 war), but 25 (since 1993, which coincides with Eritrea’s referendum.) But now, he says, we can say, “we didn’t lose, there was no loss, we recovered all our property.” He congratulates the people and the Prime Minister and, less than 3 minutes later, he says: I am finished. Then it was the Prime Minister’s turn and he speaks for more than 15 minutes. His speech included this: “… today, officially, President Isaias Afwerki has given me the responsibility of Foreign Minister so, wherever I go, if I represent Mr. Osman, don’t think of it as duplication….”

July 9, 2018: Eritrea and Ethiopia sign the “joint declaration of peace and friendship” referred to as the Five Pillar agreement by Eritrea’s Minister of Information in a tweet. The agreement jumps straight from what Eritrean government officials used to call a state of war to friendship overnight. It has no timetable for demarcation and troop removal from Eritrea’s territories which used to be, for 16 years, Eritrea’s precondition for dialog and normalization. THERE IS NO COPY OF THE SIGNED AGREEMENT ANYWHERE. All sources referring to it (UN, US Embassy, Western media, Aljazeera) have only relied on the Minister of Information’s tweet about it. Here’s how it compares with the Five Point Peace Plan Ethiopia proposed (and Eritrea rejected) in November 2014:

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)