Forget Objectivity: For The Atlantic Council, Eritrea’s Prison State Isn’t That Bad

By François Christophe, December 2016

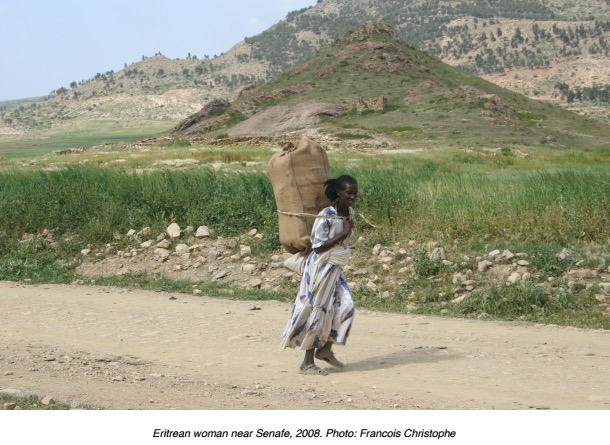

Risk analyst on sub-Saharan Africa, who worked at the French embassy 2008 – 2009

Original source with references

Eritrea is in many ways one of the world’s few totalitarian states, although you would never know it from the Atlantic Council…AC’s artful spin amounts to nothing less than revisionism.

Contrary to classic dictatorships, the totalitarian state does not simply target political opponents, but society as a whole. It methodically destroys all forms of human solidarity not directly under its control – from religious congregations and civil society organizations down to family units – in order to exert absolute rule over a population of atomized and defenseless individuals. Whereas those who do not actively oppose the government are normally safe in an “ordinary” dictatorship – they can choose to remain uninterested in politics and seek refuge in the private sphere -, a totalitarian state requires that each and every one of its citizens be entirely dedicated to its leader and official ideology. Eritrea is in many ways one of the world’s few totalitarian states, although you would never know it from the Atlantic Council.

Widely recognized NGOs as well as the UN’s Human Rights Council (UNHRC), among many others, paint a bleak picture of the human rights situation in the country. In June 2014, the UNHRC established a special Commission of Inquiry (UNCOI) to document the situation. The UNCOI concluded that the Eritrean government engages in “systemic, widespread and gross human rights violations” and that “it is not the law that rules Eritreans, but fear”. Despite “the facade of calm and normality apparent to the occasional visitor”, human rights violations by the authorities include “enslavement, imprisonment, enforced disappearance, torture, reprisals as other inhumane acts, persecution, rape and murder”. The scale of the abuse largely explains why Eritrea, which only has 3-5 million people, sent more refugees to Europe than any other country in Africa in 2015: an estimated 5 percent of the total population has fled between 2003 and 2013. In one incident among many others, on April 3, 2016, “as military service conscripts were being transported through the centre of Asmara, several conscripts jumped from the trucks on which they were traveling. Soldiers fired into the crowd, killing and injuring an unconfirmed number of conscripts and bystanders.”

Yosief Ghebrehiwet, one of the most perceptive analysts of Eritrean politics, strikingly describes contemporary Eritrea as a large-scale, multi-layered penitentiary system comprising several prisons into one in the manner of a Russian doll:

the tens of thousands of prisoners populating Eritrea’s jails make up the narrowest circle, the “prison within a prison within a prison”a broader, middle circle includes the hundreds of thousands of military conscripts whom the government uses as forced laborers finally, the outer circle encompasses the entire population, who lives in fear of arrest and is forbidden from leaving the country, hence the depiction of Eritrea as a “prison state”

An essential layer of Eritrea’s repressive system is its mandatory military service of indefinite duration, the “national service”, which conscripts often call “national slavery”. Although the national service is officially justified by the threat posed by foreign enemies such as Ethiopia, the program serves to provide the government with a constant supply of virtually free labor and “maintain control over the Eritrean population.” Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International note that agelglots (“conscripts” in trigrinya) “serve indefinitely, many for over a decade” and “up to twenty years”, despite the fact that the program is officially limited to 18 months. “Children as young as 15 are sometimes conscripted”, and all conscripts are forced to work “for government-owned construction firms, farms, or manufacturers”, for little or no pay.

According to the UNCOI, “the use of forced labor, including domestic servitude” primarily serves “private, PFDJ-controlled and state-owned interests”. Individual army generals, for instance, use forced agelglot labor to build new homes for themselves. Throughout national service, “perceived infractions result in incarceration and physical abuse often amounting to torture. Military commanders and jailers have absolute discretion to determine the length of incarceration and severity of physical abuse.” Female conscripts are often raped by commanders, a crime which goes unpunished. In the words of a leading expert on Eritrea, the national service “progressively sank into a nightmarish quagmire of exploitation resulting in quasi-slavery. Many of the young women are routinely raped, work conditions are miserable, with monthly “salaries” of 450 Nakfa ($9), no proper place to sleep, no health care, very poor food, no home leave allowed for months, and at time for years, ‘deserters’ hunted down by the army and sentenced to several months in jail followed by indefinite work periods, dangerous digging or construction jobs performed without proper security equipment and resulting in workers frequently being injured or killed on the job.”

Outside of national service, Eritreans live in fear of arbitrary arrests in the complete absence of any rule of law. Prisoners are “rarely told the reason for the arrest, and most are detained without any form of judicial proceeding whatsoever”. Detainees are held “in shipping containers, with no space to lie down, little or no light, oppressive heat or cold, and vermin”. According to the UNCOI, torture is “systematic”, a “clear indicator of a deliberate policy” to “instil fear among the population and silence opposition”. The security services also resort to enforced disappearances, in which case “friends and family of disappeared persons [are] never able to obtain information officially”. Plainclothes informants abound, part of the country’s “complex and militarised system of surveillance”.

Religious minorities, such as evangelicals, are specifically targeted and their members imprisoned. Since anyone can be denounced to the authorities with little justification, mistrust corrodes friendships and family relations. In addition, relatives can be fined, deprived of government services or even jailed as a punishment for the actions of a family member, a form of “guilt by association”. The fear of reprisals against loved ones is used to coerce Eritrean refugees abroad into paying a special government tax, despite the fact that they no longer reside in Eritrea. It also explains why those in the diaspora who take part in demonstrations denouncing the rule of President Isaias Afwerki sometimes choose to wear masks to remain anonymous. Since leaving the country is forbidden, escapees risk being shot at the border, although authorities have enabled a lucrative smuggling business, turning the Eritrean exodus into a significant source of revenue, particularly for the military.

Politically, Eritrea held no election since it became officially independent from Ethiopia in 1993. A constitution was adopted in 1996, but never implemented. “Power (…) is concentrated in the hands of the President and of a small and amorphous circle of military and political loyalists.” There are no independent media as the country’s newspapers, TV and radio channels are all government-owned and operated, prompting Reporters Without Borders to rank Eritrea at the very bottom of its international index on press freedom. “All of the independent print media were arrested” in September 2001, not long after opposition members “who had dared to publish an open letter (…) calling on the government to implement the (1996) constitution and hold elections” were also jailed. The men were never tried, but put in solitary confinement in a remote detention center, where most of them have likely died. In 2009, Isaias responded to Sweden’s requests to free Dawit Isaak – one of the imprisoned journalists and a Swedish national – by publicly declaring:

“We will not have any trial and we will not free him. We know how to handle his kind. (…) To me, Sweden is irrelevant.”

Unfortunately, you wouldn’t know any of this from reading the Atlantic Council’s analysis of Eritrea. Indeed, it is as if the AC had made it its mission to obscure what is known of the country, most notably by systematically questioning and minimizing the extent of the regime’s human rights violations. In a series of articles and interviews, AC’s Africa Center’s deputy director Bronwyn Bruton has maintained this line with remarkable persistence.

Astonishingly, the AC has authored several articles whose sole purpose is to undermine the credibility of the UNCOI’s detailed investigation into human rights abuses in Eritrea. Knowing full well that the commission was denied entry by the Eritrean government, Bruton nevertheless accuses the UNCOI of being “uninterested” in visiting Eritrea as “its conclusions were already drawn”. She bizarrely charges commission members of failing to read “the relevant academic literature”, in another unsubtle effort to sow doubt on the commission’s seriousness. In a June 23 New York Times article, comically titled “It’s Bad in Eritrea, but Not That Bad” – imagine a piece on North Korea with the same title! – Bruton blames the UNCOI for relying mostly on the testimonies of hundreds of Eritrean exiles, while simultaneously lamenting the alleged exclusion of PFDJ supporters in the diaspora – the very people who, throughout the UNCOI’s investigation, relentlessly intimidated exiles to keep them from testifying, sometimes going as far as physically preventing them from reaching the commission’s offices. In her view, the victims were clearly over-represented by the commission, whereas their tormentors should have been given more of a say.

On the other hand, it is hardly surprising that the AC would attack the UNCOI’s investigation, since it has long denied the scale and seriousness of the abuses perpetrated by Isaias’ regime. Astonishingly, the think tank has suggested that the massive exodus of Eritrea’s youth has little to do with human rights or the mandatory military service. Instead, Bruton declared:

“When Eritreans leave, they do it for economic opportunities. In order to get a green card, they have to say that they’re oppressed.”

Her statement suggests that she never asked recent Eritrean exiles why they fled. In another instance, she compares Eritrea and Puerto Rico, on the grounds that Puerto Rico experiences strong emigration to the US. Perhaps Bruton is not aware that Puerto Rico is actually a part of the US; in any case, she would have been better advised to compare Eritrea with Ethiopia, which despite suffering from poverty and having over 80 million people – compared to Eritrea’s 3-5 – produces far less refugees than Eritrea does – in fact, Ethiopia itself is home to tens of thousands of Eritrean refugees). The AC even questions the scale of Eritrea’s emigration problem, alleging that refugees from neighboring countries claim to be Eritreans to “take advantage of Europe’s asylum policies”. One can only hope that European immigration officers don’t read her work.

The AC minimizes the ordeal of those who attempt to flee Eritrea, by casting doubt on the UNCOI’s findings with regards to the “shoot-to-kill” policy at the border: Bruton claims that she has “never heard of any meaningful example that would support that claim”, discarding the testimonies not only of Eritrean refugees who reported being shot at, but also that of former soldiers who were tortured after refusing to shoot former countrymen.

Some of the claims made by the AC go against well-established facts, which suggests that their author either knows little about her subject, or engages in willful disinformation. For instance, Bruton does not hesitate to write that “charges of forced labor would be very hard to substantiate”, despite the widespread availability of evidence that the national service has long been turned into a forced labor program. She even speaks of “national service volunteers” to invoke the many thousands who have been forcibly and indefinitely enrolled in the military, which is outrageously misleading. In the same vein, Bruton nonchalantly denied any food crisis in Eritrea in her testimony at a September 14, 2016 subcommittee hearing at the US House of Representatives, which she was invited to address. Having lived in Asmara, I personally witnessed hunger in the capital, where some families resort to sending their children to beg for food at the neighbors’; and humanitarian workers agree that the situation is far worse in the countryside. In January 2009, I watched Isaias deliver its seven and a half hours long speech to the nation on official channel ERI-TV: Isaias recommended that no adult eat more than 1,200-1,500 daily calories – an amount normally recommended for children of two to four years of age. And that was his New Years speech.

One of the most bizarre and troubling aspects of the AC’s analysis of Eritrea is the idea that human rights violations may not in fact reflect a deliberate government policy, but rather the bad behavior of third parties upon who authorities allegedly have little control. In a particularly egregious example of disinformation, Bruton suggested to the House Foreign Affairs Committee that Eritrea’s totalitarian government was in fact so weak that it had little control over anything:

Representative Karen Bass: “So, what’s the human rights situation from your vantage point, from your viewpoint? What are the human rights abuses?”

Bronwyn Bruton: “I think all the human rights abuses that have been described are absolutely real. I think that the question is, and the reason that I asked the question earlier from the intelligence officer who asked, “is there a government in Eritrea?” Are these abuses systemic? Are they the result of deliberate government policy or how much are they the result of poverty, the “no-peace-no-war”, bad behavior by people outside of Asmara that the government has poor grip on, what is the relationship between the political side of the government and the military? We have virtually no knowledge of that. I have no doubt that the military are bad actors, the extent to which their behavior is condoned by the government? I don’t really know. I’ve talked to people, senior people, in the government, in Asmara and I may be super naive, but sometimes I think they believe human rights abuses don’t really exist, and if they do, they are very few and far between…”

The statement itself is a jewel of self-contradiction: notice how Bruton first states that “all the human rights abuses” are “absolutely real”, before concluding with the suggestion that they they are “few and far between”, if they even exist at all. Here, Bruton is her own parody: in her imaginary Eritrea, human rights abuses could only be the work of disembodied spirits, while the poor government remains clueless as to what is happening. This fantasy would certainly be even more amusing if it did not have the potential to cause doubt and confusion among people unfamiliar with Eritrea’s current predicament – there are many -, especially given the AC’s notoriety. Father Habtu Ghebre-Ab, who was also invited to testify at the hearing along with Dr. Khaled Beshir, rightly saw in Bruton’s statements “an effort to make the human rights situation look so much better than it really is”. In an earlier interview with VOA, Bruton reported what Isaias had told her on human rights, apparently failing to detect the cynical nature of his statement:

“He [the President] reaffirmed his attachment to equality and human rights. He says those are the fundamental qualities upon which he governs.”

Through Bruton, the AC has denounced the allegedly “disproportionate” focus on Eritrea’s human rights situation, declaring:

“In terms of repression, Eritrea is on a par with Ethiopia and Djibouti”.

To be sure, Eritrea is hardly the only country in the Horn of Africa with a less-than-stellar record of human rights abuses and political repression. In Ethiopia, where a state of emergency has recently been declared, security forces have cracked down on protesters in the Oromo and Amhara regions, killing hundreds of peaceful protesters. In a country where the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) and its allies control all of the 547 seats in parliament, Obama’s statement during his July 2015 visit to Addis Ababa that the Ethiopian government had been “democratically elected” is grotesque.

However, contrary to the AC’s stance, Eritrea’s human rights record is objectively much worse than that of both Ethiopia and Djibouti. While governments in those countries repress their political opponents mercilessly, Isaias’ paranoid, highly-militarized regime represses its entire population, forcing it to go into exile, not unlike a parasite slowly killing its host. In that sense, the Eritrean state has more in common with totalitarian regimes like Turkmenistan or North Korea than with its authoritarian neighbors. In contemporary Eritrea, one does not need to be a political opponent to end up in jail or at a labor camp.

Consider the countryside, where families depend on their children to work in the fields when older relatives are forced into the national service. To ensure their family’s subsistence, teenagers have no other choice than to drop out of school and take on farming, but doing so prompts their arrest for dropping out of school. In this situation, mothers face a bleak choice between the family’s starvation and the arrest of their children. Bruton would have US policymakers believe that Eritrea’s unique ordeal is commonplace in the region, yet not other country in East Africa has forced generations of people into indefinite, unpaid labor; banned travel and seal the borders; banned public gatherings of even a handful of people; locked up entire religious congregations; or taken entire families hostage if one member manages to leave the country. No other regime in East Africa has done so much to split families apart and prevent individuals from being loyal to anything other than the PFDJ party-state.

In some instances the AC’s analysis sounds plain naive rather than manipulative, taking Isaias’ empty promises at face value. In April 2015, Bruton enthusiastically announced:

“There is a process of change going on in Eritrea. Officials said that they have stopped the indefinite conscription policy. (…) They say that only 5% of the conscripts have been there for more than 18 months at this point. I suspect that the release of those people may be one of the things that’s driving the outflow of refugees from that country.”

Although high-rank Eritrean officials regularly promise to end indefinite conscription and limit it to its legal duration of 18 months – a promise reiterated to convince the Europeans to contribute 200 million euros to Eritrea’s development between 2016 and 2020 – such commitments have all come to nought. The government has yet to send the slightest signal that this would actually happen, and in June 2016 Eritrean Foreign Minister admitted that conscription would continue to last over 18 months “to defend the country” against perceived threats from Ethiopia. Bruton has also proven quite eager to appropriate the government’s narrative of social and economic progress, as if it could somehow compensate for the repression and lack of freedom, declaring:

“The education system, the health care… It’s amazing how much Eritrea has managed to accomplish in spite of its isolation. I have to say, I was astonished.”

In spite of these accomplishments, Bruton is concerned that the UN-imposed sanctions against Eritrea’s government are “hurting”, although they consist in little more than an arms embargo, as well as a travel ban and asset freeze targeting high-ranking officials.

Finally, when it comes to policy recommendations, the AC is no stranger to contradiction. It rightly blames the US for putting strategic considerations above human rights in its dealings with Ethiopia, yet forcefully argues in favor of doing just that in Eritrea: urging US policymakers not to be misled by “the narrative of crushing government repression”, and to mend ties with the authorities in Asmara, which would be “in the interest of both nations”. It seems the AC is concerned with human rights violations after all, or at least those taking place in Ethiopia.

The AC’s motives for consistently painting a totalitarian regime in a favorable light are a matter of speculation. Bruton herself is primarily a Somalia expert, who only started to focus on Eritrea in 2014-2015. It is likely that in contrast to Somalia’s chaos, she found Eritrea’s totalitarian orderliness somewhat refreshing. Puzzling as it sounds for a think tank whose mission includes providing policymakers with objective analysis, it is entirely possible that the AC’s open, unapologetic bias toward Isaias’ government is grounded in genuine conviction. It is very clear that Bruton was truly impressed by her meeting with the Eritrean president in the spring of 2015. In the interview she gave VOA upon her return, her admiration is unmistakable; in fact, her tone is not that different from that of, say, a teenage girl describing her latest crush:

“[Isaias] was very impressive. We sat with the President for almost three hours. He was very, very sharp. I was very impressed. He was so astute, he was so articulate in English. Frankly, he looks 50, and he’s a lot older than that.”

Let’s pause for a moment to remember just who Bruton is talking about here: that’s right, it’s the very guerrilla leader who eliminated his guerillero companions, and, once he became President, locked up journalists for them to slowly die of diseases in shipping containers, sent his country’s youth to be killed in the trenches, replaced universities with military training camps, and lets his army generals sexually assault young female conscripts… the list goes on. A progressive leader, indeed.

Beyond personal admiration, Bruton’s articles and statements suggest another reason for her consistent support for the PFDJ ’s regime: she revels in deconstructing what she scornfully names the usual “narrative” on Eritrea, which according to her revolves around a “disproportionate” concern for the country’s human rights situation. Bruton badly wants to be the smartest person in the room, which predisposes her to embrace a contrarian stance. As she warns her audience against a supposed anti-Eritrean bias, she exudes a sense of superiority not unlike that of conspiracy theorists, who derive great pride from being “the only ones who understand what is happening, the only ones who get it”.

Alas, far from any intellectual heights, Bruton’s points are not exactly groundbreaking or new, since most of it comes straight out of the PFDJ’s instruction guide to its supporters worldwide. In the introduction to its 2016 report, the UNCOI lists the objections it has received from regime supporters in the diaspora. Strikingly, almost all the key critiques identified by the UNCOI have been expressed in one form or another by Bruton herself. In other words, a lot of the AC’s work on Eritrea really amounts to a simple rewriting of PFDJ talking points, in an unsuccessful effort to give them a more legitimate, more academic, and less partisan appearance. The UNCOI notes that the “common themes” it found in the correspondence of its critics include:

- The detrimental impact of UN sanctions on the humanitarian situation in Eritrea

- The absence of rape in Eritrea

- The failure of the commission to ensure implementation of the decision of the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission on Badme

- The justification of indefinite military conscription in Eritrea by the threat from Ethiopia

- The history of inter-ethnic and inter religious harmony in Eritrea

- The absence of a shoot-to-kill policy at Eritrean borders

- The progress made by Eritrea on the Millenium Development Goals

And here are the corresponding points, as expressed by Bruton:

- “(…) continually adding stress to the current regime in Asmara, for example through sanctions and indictments, is likely to simply make Eritreans more miserable without producing any real change.”

- “[The UNCOI’s report] extrapolates from anecdotal examples — like instances of rape by military forces — to allege systemic abuses and blame them on state policy.” (here Bruton does not deny that army generals have committed sexual violence against female conscripts, but brushes off such cases “anecdotical”)

- “Since then, for the past 15 years, Ethiopian troops have been permitted by a silent international consensus to flout the treaty and illegally occupy Eritrean territory. (Bruton is factually right here)

- “The presence of Ethiopian troops on Eritrean soil has done crippling harm to the Eritrean people. (…) The presence of this ‘army at the gates’ has of course undermined Eritrea’s political development. The over-militarization of the country as a justified means of defending the country has had severe consequences for political and civil space.” (In reality, the border dispute with Ethiopia does not explain why Eritrea’s entire population is still kept on a war footing today, deprived of its civil and political rights)

- “Despite the virulent tribal and ethnic conflicts plaguing the rest of the region, the Eritrean government appears to have been exceptionally successful in its own nation-building project. Eritreans seem largely unified across tribal and religious categories.”

- “The COIE’s claim that Eritrea maintains a “shoot to kill” policy on the border is an especially egregious example—I’ve never heard of any meaningful evidence that would support that claim, except perhaps in a few, highly militarized spaces along the border, where Eritrea is actively in conflict with its neighbors.”

- “The United Nations Development Program gives Eritrea high marks for its progress on several Millennium Development Goal.

Naturally, given its sustained tendency to stick to the PFDJ party line, regime supporters in the diaspora have fallen in love with the AC’s analysis of Eritrea. Bruton herself became a favorite of the regime’s army of online supporters, who all happen to be based in the West and frequently team up to launch coordinated, targeted attacks one anyone who dares to criticize the Eritrean government on social media. The US-based Tesfanews, which repackages official propaganda for its consumption by Eritrean expatriates, praises Bruton and shares her articles in full. Bruton herself does not seem to mind the attention from the PFDJ crowd. On the contrary, in August 2015 she addressed the annual conference of the YPFDJ, the Eritrean party-state’s youth organization… in Las Vegas (that’s right, the same party which calls for “victory to the masses” has annual meetings in Vegas). No researcher with even a modicum of concern for apparent bias would do the same.At a time when Eritrea appears to have embarked on a public relations effort to improve its image in the West, the AC’s activism is a godsend. Although evidence is hard to come by, several consulting firms may already be enlisted in this effort in the US, where a leaked memo dated from January 2015 revealed that former US Ambassador Herman Cohen had been engaged by the Eritrean embassy to lobby on behalf of Asmara and “disseminate truthful information”. Eritrean embassies in the West have also attempted to enlist reporters, with mixed success. On June 28, journalist Pierre Monegier revealed that he was offered 15,000 euros and a free trip to either New York or Tokyo in exchange for painting a rosy picture of Eritrea in his news report for the French public television. After he refused, Eritrea’s embassy to France set up a conference with the help of mysterious consultants armed with fake Twitter accounts to discredit Monegier’s work.

In 2015, the AC’s complacency toward the Eritrean government earned it the generous financial backing of a Canadian mining firm, Nevsun, which operates exclusively in Eritrea – providing the government with much of its foreign exchange income – and has a high stake in improving the country’s image. Based on figures disclosed by the AC itself, the company’s donation ranged from USD 100,000 to 249,000. Contacted by French journalist Leonard Vincent, a Nevsun representative made the following statement:

“Nevsun made a contribution to the Atlantic Council last year because we were impressed by their ongoing constructive work on Eritrea.”

Nevsun’s statement makes no mystery of the fact that its donation is directly related to the AC’s singularly positive outlook on Eritrea. And although Bruton stated before the House Foreign Affairs Committee that she had “no direct relationship with Nevsun”, she spoke alongside Nevsun Vice President Todd Romaine at the Las Vegas YPFDJ conference.

Atlantic Council’s Africa Center’s deputy director Bronwyn Bruton and Nevsun VP Todd Romaine speaking under the banner of the YPFDJ, the Eritrean party-state’s youth organization, at the YPFDJ’s 11th annual conference in Las Vegas, August 2015

To anyone familiar with Nevsun, a company which, according to a mounting body of evidence, relied on slave labor to build and operate its Bisha gold mine, it is quite puzzling that the AC was even willing to potentially damage its own reputation by being associated with such a problematic donor. On October 6th, the Supreme Court of British Columbia ruled that a case against Nevsun brought forth by former mine workers would proceed in a Canadian court, allowing the plaintiffs to have their case heard. However, a lot has already been established about the company’s practices, contrary to Bruton’s claim that past allegations against Nevsun were dismissed.

One of the world’s leading expert on Africa is the author of a report on Nevsun and working conditions at the Bisha mine. Although the report has not been made public, its author, who is familiar with the AC’s writings on Eritrea, gave me permission to quote from it. The information on working conditions at the Bisha mine comes both from former national conscripts who were assigned to work at the mine, and subsequently managed to flee the country, and from foreign contractors – such as Mike Goosen of the South African construction management firm Senet – who have testified to confirm the conscripts’ account. The conscripts were not directly employed by Nevsun, but by a state-controlled intermediary, Segen. However, for at least several years Nevsun used those conscripts to build its mine. In the words of the aforementioned expert:

“Nevsun has said that it does not employ national service conscripts, which is true if by ’employ’ we mean ‘hire as a salaried member of work force’. However, Nevsun [relied on] the Segen Construction Company (…), a government-owned company which does ’employ’ conscripts under terrible conditions. Nevsun knew it (…)”

The conditions described by formers Segen workers include sleeping on the ground in a malaria-infested area, while surviving only on lentil soup and bread during the day. Therefore the workers who built the mine were “continuously hungry”. At one point, Mike Goosen arranged for cooks at Nevsun’s main camp to set food aside for the conscripts, but Segen managers promptly put an end to it. Several workers reportedly died of heat stroke in the scorching heat of the western Gash-Barka region, where temperatures often exceed 95 farenheit degrees.

By 2012, Nevsun, realizing that the use of forced labor by Segen constituted a threat to its own reputation, started to require that the workers it directly employed were “free of national service obligation”. All of them were, which is unsurprising since those workers employed directly by Nevsun were not forcibly enrolled; in fact, Nevsun jobs were probably quite coveted due to the comparatively high pay and the protection from the abuse routinely inflicted on army conscripts at Segen. One chilling case makes clear that female conscripts at the mine were routinely exposed to sexual violence, like their national service peers elsewhere:

“[A female Nevsun employee] was raped by soldiers who believed her to be a conscript. When the soldiers searched her belongings and found a card identifying her as a Nevsun employee, they stopped molesting her, released her and even apologized.”

To this day, it remains unclear whether Nevsun ended its collaboration with Segen. From the start, it was the Eritrean government which demanded that Nevun use Segen as its primary contractor for the construction of the mine. In a video posted on its website, Nevsun claims that:

“(…) in Eritrea, it is illegal to use national service workers in the mining sector, so all perspective employees are screened before they are hired” and “contractors are also prohibited from using national service workers”.

This clearly did not apply to the company’s primary contractor, Segen. Moreover, Nevsun’s defense should be considered with all the more skepticism that company representatives have a record of making inaccurate statements:

“When asked about the median age of the Nevsun workforce, the answer was ’60’, a most unlikely figure for a mining workforce, and one which can be disproved by a simple glance at Nevsun’s own website, which displays only young and fit workers”.

Despite that fact that Eritrea has no independent justice system, Nevsun’s lawyers have long argued without irony that only an Eritrean court was qualified to examined the former workers’ accusations. Perhaps this is because the company has already had its share of lawsuits in Canada: it 2012, it was forced to pay “$12.8 million, in compensation for having overvalued the mine’s reserves in order to boost the share price before off-loading massive amounts of stock at an exaggerated price”.

In light of the available information and the pending Canadian trial, why would the AC even want to be financially associated with a company like Nevsun? Perhaps this should not be a surprise for a think tank whose leading Eritrea expert believes that things “are not that bad” in the country. Perhaps that, having already lost any pretense at objectivity on this topic, the AC literally had nothing left to loose by accepting Nevsun’s money. And to be sure, in the months following the donation, Bruton only carried on her “constructive work on Eritrea”, in the words of the company itself.

Perhaps this just part of a troubling trend for the AC. As Foreign Policy recently reported that the think tank intended to offer its “Global Citizens Award” to Gabon’s President Ali Bongo, even as the latter was suspected of resorting to fraud to ensure his Aug. 27 reelection (the country’s post-election crisis eventually forced Bongo to miss the award reception in New York). Yet, as unsavory as Bongo’s regime may be, Eritrea is far worse, and the AC’s artful spin amounts to nothing less than revisionism.

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)