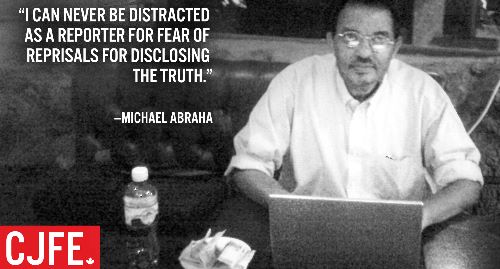

Q&A: EXILED JOURNALIST MICHAEL ABRAHA ON PRESS FREEDOM IN EAST AFRICA

Michael Abraha is an experienced journalist born in Eritrea, now based in Kenya. He began his decades-long career in his home country but had to flee under threat of arrest because of his work.

Eritrea is arguably the worst country in the world for press freedoms; it is ranked last out of 180 countries on Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index. It imprisons more journalists than any other African country, and systematically violates freedom of the media, expression and information. Since leaving the country, Michael has lived and reported in Kenya, South Sudan and the United States; renewed threats upon his attempt to return to Eritrea as a journalist forced him back into exile for a second time.

Through CJFE’s Journalists in Distress (JID) Fund, Abraha received an emergency assistance grant that helped him move to a safer neighbourhood in Kenya, where he has continued to face threats for his reporting from what appear to be non-state Eritrean actors and supporters, as well as South Sudanese and Kenyan officials. CJFE talked to Abraha about press freedom in East Africa and the persecution, attacks and fears he has faced as a journalist.

TELL US ABOUT YOUR WORK. WHAT TYPE OF REPORTING DO YOU DO?

In recent years, I have been writing mainly about the topics of free press and free speech, which we know are vital for democratic and economic development in Africa.

Real and steady growth is assured in systems where there is a free flow of information, and particularly where people have access to state information. But under the pretext of national security, the press is routinely suppressed in Africa, especially by autocratic regimes like those in Equatorial Guinea and Burundi. In war-torn countries such as Libya, where reliable information is sorely needed, journalists are threatened, attacked and killed by political rivals and militias. I stressed the key role of a free press in my recent article on Libya, “Libya Media: Stuck in a Quagmire,” published by the Doha Center for Media Freedom.

I have also done hundreds of articles and interviews with experts over the last 10 years that focus on the urgent need for domestic policy changes in Eritrea, for instance, improving its justice and prison systems.

WHAT MADE YOU INTERESTED IN JOURNALISM? WHY HAVE YOU STUCK WITH IT, DESPITE REPEATED THREATS AND ATTACKS?

Nothing is more challenging and exciting for me than being a reporter or commentator, describing and interpreting current history. I have always believed that journalists have a chance to take part in building a saner, safer world. It was this belief that drove me to shift in the 1980s from a more stable and lucrative law practice to the riskier profession of journalism.

As a young reporter I was fascinated by the idea of using words and phrases skillfully—fitting them together like a house builder lays bricks to create a beautiful structure. I find this artistic and creative aspect of journalism truly exhilarating.

Journalism can also be full of fun. For example, I once seriously angered Ugandan dictator Idi Amin when, during an exclusive interview, I deliberately breached protocol and addressed him as “Mr. President” instead of his full title (His Excellency, President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji Doctor...).[1] Another time, I photographed Ethiopian dictator Mengistu Hailemariam's new French-made, high-heeled shoes that made the 5' 4” tyrant appear taller.

Of course, journalism is a serious and sometimes risky business. There have been two assassination attempts on my life in the last two years, both directly linked to critical articles I had written. Despite these and other threats, I plan to continue my journalism for as long as I am alive. Journalism is more than just smart ways of presenting the news or analyzing issues, as important as this is. I am guided in my work to be an effective messenger by the higher ethical values of integrity, unselfishness and honesty.

Thanks to CJFE's Journalists in Distress emergency assistance, I have relocated to a safer home in a peaceful neighborhood in Nairobi, where I can continue my work. I was uplifted and encouraged by CJFE’s solidarity, timely support and trust in my journalism.

YOU REPORTED TWO ASSASSINATION ATTEMPTS ON YOUR LIFE IN THE LAST TWO YEARS. CAN YOU DESCRIBE THEM?

The first one took place on April 8, 2014: four bribed Kenyan police officers led by a foreign agent raided a Nairobi hostel where I was staying. The plan was to abduct and then execute me, according to the confession of the foreign agent before he mysteriously died two months after the assassination attempt. The case is still under investigation.

The second incident occurred on August 21, 2015: unknown assailants broke through my window and hurled a heavily nailed wooden frame on my bed in the dark. Luckily, I was not on my bed at the time. The attackers then took my laptop and two cell phones but did not take cash or other valuables.

To me, the cases appear connected but we have to wait for the findings of the Kenyan investigators.

WHY DID YOU FIRST LEAVE ERITREA IN 1986? DO YOU HOPE TO RETURN FOR A THIRD TIME?

I was alerted by colleagues that there was a secret order for my arrest and execution for giving out famine-related information to foreign journalists. Eritrea was still part of Ethiopia in 1986, and was recovering from the 1983-85 famine disaster during which over a million people reportedly perished while the communist government spent millions of U.S. aid money to commemorate its tenth anniversary.

The privately owned, international radio station for which I worked as a senior broadcaster had been nationalized by the regime; as part of the state media, I knew too much about people dying of hunger while the regime was initially trying to hide it. I was accused of passing on to Western journalists the fact that the government was diverting foreign food aid and medicine to its armed forces instead of delivering it to starving people.

I fled the country within days, with the help of a church organization, and was later granted refugee status and citizenship in the U.S.

I returned to independent Eritrea in 2004 with the intention of settling there on a long-term basis, and immediately realized that discussions about politics and the media were completely forbidden. This was very hard for me since journalism had become a way of life and I feared I might get in trouble for asking the wrong questions—many dissenting politicians and independent journalists were put behind bars on treason charges after the 1998-2000 war with Ethiopia. But I took the risk of still talking and discretely asking questions wherever possible. In six months, I only managed to write one article, which I published in the U.S. under a pen name, before fleeing again.

I love my adopted home, the U.S., where I have spent most of my adult life. But Eritrea is where I was born and grew up. I would have loved to return and start a free and independent media house there. Free, responsible journalism is key for Eritrea's steady and peaceful growth.

WHAT HAVE BEEN THE MOST REWARDING EXPERIENCES OF YOUR JOURNALISM WORK? THE WORST?

The most rewarding experience was my time in Juba, South Sudan, where I was invited by a government minister after the country gained independence in 2011 to serve as chief news editor for his newspaper, The Pioneer. I had a staff of 10 reporters and commentators. Some of my trainees there became very successful as print and broadcast journalists, such as Michael Thon Mangok, who went on to host the most listened-to political program in the country at Bakhita Radio.

The second most rewarding experience was when I started The Eritrean Monthly magazine in 1994, published in Berkley, California. Covering Eritrean and African affairs, it may have been the first privately owned independent Eritrean publication since the country's independence in 1993.

The worst part was when I lost everything during an outbreak of violence in South Sudan in December 2013, including my laptop, camera, mobile phones, money and many personal belongings. I was hurriedly evacuated to Nairobi for safety. The South Sudanese government official who had invited me to Juba actually fled the country, leaving me and other staff members at his newspaper without pay. The official, who was once a journalist himself, was already ten months behind in making these payments. This experience made it difficult to start anew as a professional journalist in East Africa.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS WITH BEING A JOURNALIST IN EAST AFRICA RIGHT NOW?

The Eritrean and Ethiopian media freedom restrictions are widely reported by media rights groups and Western mainstream newspapers. Censorship remains grim. In liberal, democratic Kenya, censorship is very subtle and often self-imposed. In January, the Kenyan Daily Nation, one of the most influential newspapers in Africa, fired one of its top editors, Denis Galava, for criticizing President Uhuru Kenyatta's government. Galava broke no laws or regulations—critics say the action occurred because the newspaper feared it would lose revenue from extensive government ads.

Another very troubling development in East Africa is the deteriorating situation in newly independent South Sudan. Last year alone eight reporters were murdered, one of whom I knew well. The former South Sudanese guerrilla fighters now running the country appear increasingly intolerant of criticism from journalists.

In addition to such pressures, one other very common danger for journalists is intimidation, arrests and detentions for reporting on corruption or governments' handling of Al-Shabab's terrorist attacks.

WHY ARE JOURNALISM AND PRESS FREEDOM SO IMPORTANT?

A free and independent press is crucial for a country to enjoy lasting peace and prosperity. Free press should not be written off as distractive nuisances but as a challenge for the government to do better. It is an essential concept, which Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta once aptly termed an essential fourth branch of government. Journalists are, without a doubt, the best facilitators of debates and discussions on political and social issues, thereby stimulating public participation in the management of their nation.

[1] Ugandan dictator Idi Amin’s full title is: “His Excellency, President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji Doctor Idi Amin Dada, VC, DSO, MC, Lord of All the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Seas and Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular.”

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)