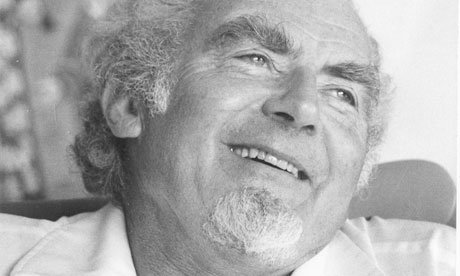

BASIL DAVIDSON: A Tribute

BASIL DAVIDSON

1915-2010

A Tribute

Basil Davidson’s contribution as a writer and historian on Africa is without parallel in Europe. His active study and active involvement in the politics of liberation was also outstanding. Everyone concerned with understanding Africa ofwes an enormous debt to his life’s work

Basil Davidson’s contribution as a writer and historian on Africa is without parallel in Europe. His active study and active involvement in the politics of liberation was also outstanding. Everyone concerned with understanding Africa ofwes an enormous debt to his life’s work

Basil had established himself as a journalist before and after World War II. During the War he saw guerrilla struggles at first hand as a British liaison officer to anti-Nazi partisans in Yugoslavia and northern Italy. In broadening his writing beginning in the 1950s to concentrate on Africa, he was to make major contributions in three areas: first in African history, then the studies of liberation movements, and understanding the nature of post-Independence African politics. His insight into national liberation struggles came about from the mid-1960s when Basil made a series of daring safaris into areas liberated by the emerging nationalist movements in Guinea-Bissau, Angola and Mozambique, and much later in Eritrea. He reckoned he walked 600 miles in the four visits to ex-Portuguese Africa (Jeremy Harding in London Review of Books, 5 August 2010).

Basil & Eritrea

In the late 1970s Basil began to engage with the Eritrean liberation struggle, and after reflection he took the position that Eritrea should not be denied the chance for ‘self-determination’ enjoyed by all ex-colonies in Africa. Of course liberation from Ethiopian over-rule was a much more controversial issue than the support of anti-colonial struggles in southern Africa. His writings on the liberation movements in Guinea Bissau, Angola and Mozambique and his support for liberation of the settler colonies in Zimbabwe, Namibia and South Africa had met an automatic resonance on the left and among young people, and in Pan African circles, which no longer came into play over Eritrea. Ethiopia was caught up in a proxy conflict of the Cold War, with the US its enemy. As one old guard fellow-traveler MP said when Basil made the case for Eritrea to the Africa Committee of the Labour Party: “I hear what you report, but at the end of the day I simply ask myself what side Fidel is on!” In Africa circlesf the Eritrea case for self-determination against their enforced incorporation into a unitary Ethiopian state was seen as promoting secession and fragmentation of an African state. Only a few radicals, such as Ruth First, shared Basil’s courage in espousing this cause.

He was involved in the first public raising of the Eritrean question in the West, a conference in London in 1979 initiated by Bereket Habte Selassie, and they co-edited the proceedings1. Thereafter, Basil was contacted on occasions by the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front seeking endorsement of specific positions or requesting he speak at some event, but he told them, like others, he did not feel able to go beyond his initial stating they had just cause without more information of their struggle. He cited the pattern that had grown up in relation to Guinea Bissau with Amilcar Cabral sending briefings, and eventually invitations to visit, to Basil and others giving solidarity. It took a couple of years before Basil’s suggestion was acted upon, but networks were gradually established, leading to a ‘seminar’ in the liberated areas in f1983, once the throwing back the last of Ethiopia’s several Offensives made that possible. And one result was the setting up of the Research and Information Centre for Eritrea (RICE) with offices in Rome and Brussels, the beginnings of an archive and a monthly newsletter, which was a partnership between EPLF and its ‘friends.’ Ultimately, this work and the archive were built on in setting up the Research and Documentation Centre in Asmara after liberation. As word spread and more ‘friends‘ had made their own visits, a more considered volume on different dimensions of the struggle was put together in 1988 at the suggestion of the EPLF with Basil co-editing2

Basil used his considerable reputation in the cause of solidarity. He spoke to the Labour Party Africa Committee, which did take an official position of support for the Eritrean liberation. He also made representations to Cuba, where his efforts to support the cause of liberation in Angola, especially, were well known, to question its support of the Derg regime in Ethiopia and thus its indirect bolstering of efforts to suppress the Eritrean liberation cause (Cuba had a military presence in Ethiopia but, unlike the USSR, did not allow its personnel toF be involved on the Eritrea front).

Basil was not able to attend the 1983 seminar but did eventually make the arduous trip into what the Eritreans called the ‘Field’ in 1988 and was able to witness the decisive battle of the liberation war at Afabet, where the EPLF forces broke out of their 10 years of encirclement. He even broadcast from the battlefield just after the victory direct to BBC World Service in London on a line the EPLF had managed to set up, announcing “the most significant conventional battle in the Third World since the Vietnamese liberation forces defeated the French at Dien Bien Phu.”

With the achievement of statehood in 1993, Basil was one of the invited guests at the Independence celebrations in Asmara. At a small informal party for the international ‘friends’ he gave a brief inspiring speech in replying on their behalf to remarks by President Isaias Afwerki. The latter had said rhetorically that what Independent Eritrea would continue to require from friends was ‘criticism.’ Whether he meant it or not, Basil made some cautions about the future at a seminar a few days later when he was invited to give his views to an audience that included many senior party leaders about the lessons from the post-liberation experiences of other African countries. His main advice was the need to avoid the institutional crises that resulted from the gap between leaders and people through encouraging those traditions of participation and answerability built up in the years of struggle. I was able to unearth the notes I had taken at the time to pass back to Basil when emissaries from the regime came to pay a ‘courtesy call,’ presumably to keep him ‘on side’ after the war with Ethiopia, 1998-2000, and after the most authoritarian moves occurred in 2001. He reminded them of his earlier warnings at that time. He also made public his criticisms of the authoritarianism and imperviousness to criticism that now characterized the regime, notably in one of his last writings in the Introduction to collected material by another ‘friend of Eritrea,’ Dan Connell3.

One ridiculous but sad moment during the Independence celebrations was when Lady Trumpington, a junior foreign office minister who was the official representative of Mrs. Thatcher’s government, came across a hotel lobby to greet two people who looked to be her compatriots, and when Basil introduced himself, her immediate response was to blurt out, “Aren’t you the fellow traveler?” Even her foreign office minder looked embarrassed by this instinctive bluntness, although someone like him had presumably prepared the briefing for her containing that categorization – evidence that he was still seen in these terms by UK officialdom. Basil’s coldly polite response was to ask whether she understood the significance of what we were all there to celebrate, the victory of a movement that was independent in all senses, against a Soviet-backed counter-insurgency – a struggle he had supported for years in the teeth of severe criticism by the communist-influenced left.

His recognition of the harsh realities of post-colonial Africa, and of the limited impact of ‘popular struggles,’ in southern Africa and then in Eritrea and Ethiopia, led him to interrogate the earlier work of himself and others. He posed the question “what explains this degradation from the hopes of newly regained independence?” His specific answer, in one of his most important books, was even more basic than a failure of leadership; it was rooted in a “crisis of institutions.”4 This work delves back into post-colonial history but comes up with a contemporary thesis. He argues that the universal pattern of equating ‘national’ independence as a project within existing colonial states, what he calls ‘nation-statism,’ ensured that it became a ‘modernising’ project, following liberal democratic norms (though not of democracy), eliminating any prospects of building on any indigenous roots, and inviting either a new form of chronic tribalism or unqualified repression in the name of unity. This work deserves to be kept alive within current discourses on politics in Africa, not least about Eritrea. He repeated the same question about post-Independence developments there in the Connell Introduction.

His contribution to Eritrea’s liberation struggle will always be recalled, and this is why some of the detailed incidents along that path are recalled here. But his insights and his method of inquiry into what went wrong may offer a continuing legacy.

Lionel Cliffe,

September 2010

1. B. Davidson, L. Cliffe & B. Habte Selassie, eds., Behind the War in Eritrea. Nottingham, Spokesman Books, 1980.

2. L. Cliffe & B. Davidson, eds., The Long Struggle of Eritrea for Peace & Self-determination. Trenton N. J.: Red Sea Press, 1988.

3. B. Davidson & L. Cliffe, ‘Introduction’, in D. Connell, Building a New Nation: Collected Articles on the Eritrean Revolution. Vols. 1 & 2, Trenton, N. J.: Red Sea Press. 2004: xiii-xvi.

4. B. Davidson, Black Man’s Burden: Africa and the Curse of the Nation-State .London: James Currey, 1992.

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)