Eritrea: Tewahdos’ Complicity in the Demise of their Church

Eritrea's Tewahdo's Complicity in the Demise of their Church

Yosief Ghebrehiwet

This article was posted in Asmarino.com on May 2008. I am reposting it today, with three issues in mind: (a) the Annual Repot of USCIRF, with its drastic recommendations, entirely arrived from the ongoing religious persecution in Eritrea; (b) the rapid closing down of Tewahdo churches due to lack of priests, as many of them are being forcefully conscripted into the army; (c) and the frayed Tigrigna identity that made the demise of the Tewahdo Church possible. I am particularly interested in the last point because I am writing an article for Independence Day that makes frayed identities one of its central premises, and thought this article would be a good introduction to it.

As you keep reading, dear readers, please keep in mind that this article was written two years ago; temporal contextualization is essential in understanding it properly. Except for the word “Eritrea” appended to the title, the article is being reposted exactly as it was written then.

An all out assault against the Tewahdo Church has now been going on for years: its reform-minded pastors thrown behind bars; thousands of its youth prohibited from attending Sunday School; its Patriarch vilified, demoted and house-arrested; its monasteries raided (“giffa”) in utter contempt to tradition and religion; its priests and monks forcefully conscripted into the army; its administrative body overtaken by a layman; its leaders hand-picked by the Isaias regime; its progress in reform totally reversed by regressive forces; its very structure drastically altered from top to bottom to fit Shaebia’s evil designs; its body isolated from its parental Coptic Church in Alexandria; etc. Yet, among the Tewahdos, no sense of outrage can be detected; none at all. It is as if all this is happening to an entity totally alien to themselves; they perversely keep watching from a distance as this tragedy keeps unfolding in front of their eyes. The confusion, indifference, paralysis and apathy displayed by this population group have no parallel among all the religious groups in the nation. Despite the fact that Shaebia has consistently shown that it holds the Tewahdos in the highest contempt imaginable, it is this very population group that remains beholden to that romantic image of ghedli the most, and keeps allowing this criminal organization to conduct one social experimentation after another upon itself with impunity; all in the name of “Eritrea.”

Lately, the regime in Asmara has gone as far as making the forced conscription of deacons, priests, monks and church leaders into the army official. The “Christian Post” (April 24, 2008) reported on this matter, “… The majority of church leaders [of the Orthodox Church] … are now required to go to military training camps .... St. Mary had 96 ministers, but only 10 of them were issued IDs that exempted them from military training. Similarly, in rural areas, where most Orthodox churches are located, the maximum number of priests and deacons allowed to serve in any church is 10. The rest are expected to report for military service if they are under the age of 50. Besides churches, the new campaign also forces many in Orthodox monasteries to be conscripted into the army.” This is unprecedented in the 17 centuries of Church history in the region; no other leader or government has ever attempted such a sacrilegious act. How did it come to all this?

The Tewahdo Church is the only religion that has allowed itself to be totally infiltrated by the government. This can easily be seen from the fact that the conscription of the clergy into the military is now being singularly applied to it. Here is what the “Christian Post” added, “The Roman Catholic Church in Eritrea was the only church to express strong public opposition to the unprecedented action … In contrast, top leaders of the Eritrean Orthodox Church, who were hand-picked by the government, readily agreed to the new policy.” How have the Tewahdos come to allow this?

As I have pointed out before in my writings, almost all the ills that have been stoking the Eritrean masses can be traced to one tragic confluence: that of the culture of abuse of ghedli with that of the culture of conformity of the masses. To each of these cultures, many contributing strands can be mentioned. But in this article, I will confine myself to looking at the meeting of two strands only, one from each, in the all-out assault against the Tewahdo Church that Shaebia has successfully unleashed: (a) Shaebia’s vulgar pragmatism, one of its most potent weapons in its arsenal of abuse; (b) and the Tigrignas’ weak and confused sense of identity that is to account for their tendency to romanticize and embrace the ghedli-concocted identity (best exemplified by the Tewahdos), one that often gives in to the slightest bit of coercion and manipulation.

[Again, in this article, I am taking a detour even though this too can be construed as part of the “romanticizing” phenomenon I have been straining to explain. I am taking this detour as a result of two recent events: (a) the news in the “Christian Post” on the official mandatory conscription of the clergy of the Orthodox Church into the army; (b) and the report on the tragic state of Patriarch Antonios recently posted in asmarino.com.]

Shaebia’s vulgar pragmatism

Shaebia is very much known for its vulgar pragmatism, but a pragmatism nevertheless. It is vulgar because whatever it does is guided by NO higher economic, social, cultural, ethical, political or ideological principle; this “pragmatism” is nihilistic to the core. The single objective of this pragmatism always remains the same: “Self-preservation above anything else!” The means of achieving this objective is: “Whatever it takes!” or “Anything that works!” The only inhibiting question that it asks in pursuing this objective is: “Can I get away with it?” In the process of doing so, nothing else matters; even the nation’s very existence is fair game.

The despot of Asmara is not as irrational as we make him to be. Even the most outrageous steps he takes are done only after carefully testing the waters. This is especially so when the step entertained is thought to be very sensitive. True to his vulgar pragmatism, the only question that he asks as he ventures into one social experimentation after another is: would they let me do it? And to find out, like a meticulous scientist, he carefully conducts his social experimentation starting from a relaxed one, working his way up to the stringiest one; always sizing up the situation as he increases the pressure incrementally. At every incremental level, he keeps testing the waters by carefully assessing the reaction of the masses. If we look at how he handled two very sensitive cases – that of G-15 and that of Patriarch Antonios – we will notice that it took him a long stretch of time in each case to accomplish his mission, a step by step approach that kept constantly testing the people’s level of tolerance.

Given the above, it is no wonder that Shaebia prefers to conduct its social experimentations first and foremost on one ethnic group – the Tigrigna – that has so far shown no sense of outrage when it comes to the brutalization of its various population groups: its womenfolk, its peasants, its heads of families, its exiled youth, its minority churches, its main religious denomination, its Patriarch, etc. No wonder that the more this population lets him do whatever he wants, the more the despot demands of it. And the more the Tigrignas let themselves be Shaebia’s guinea pigs, the more contempt the tyrant has for that population and the more brutal get his experimentations.

Testing waters

If we look at how the tyrant worked his way up in the scale of abuse – from defamation to outright arrest – in the cases of G-15 and Patriarch Antonios, we can notice striking similarities. Both required a careful step by step approach that took a substantial amount of time to accomplish what he set out to do. In the case of Patriarch Antonios, it took him more than two years to go through carefully orchestrated steps to finish his demonic job. These incremental steps were structured with the public’s reaction in mind; he never took any step without testing the waters first. Here are the four steps that he took in the cases of G-15 and the Patriarch:

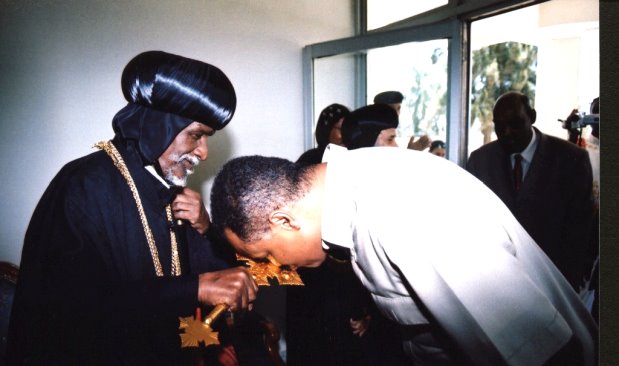

First, aspersions are cast, with no official statements to back them up. The Shaebia mill of rumors is set in full motion, with the targeted individuals as having fallen out of favor of Isaias for doing this or that. This is done with the aim of gauging the opinion of the man on the street. In the case of Patriarch Antonios, this initial stage started with the Patriarch’s courageous stand against the unsolicited incursions into the Church’s domain by the tyrant. The Patriarch refused to close down the Sunday School of the Medhanie Alem Church (a magnet to thousands of youth), confronted the tyrant and demanded that the detained pastors be released and strongly objected to the fact that a layman (Yoftahe Dimetros) was assigned by the regime to administer the Church. It is these three events that triggered the incremental assault on the Tewahdo Church. Of course, Shaebia’s defamation process started where it matters most – among the clergy – before it ventured out among the public.

Second, the targeted individuals are demoted, “frozen” or relegated to positions where they are rendered impotent. Then the tyrant lets a significant amount of time to pass without taking a major step to see how the public would react. If the public doesn’t seem to care either way, it is time for him to go one step further. And this is exactly what the despot did with Patriarch Antonios. He sent his hit man Yoftahe Dimetros to set this process in motion. The first thing the errand boy did was to take away all the administrative power from the Patriarch, rendering the power of the Patriarch impotent. This was a necessary move in laying the ground for the “divide and conquer” strategy that was soon to cause havoc in the Church. This waiting game was made not only with the Tewahdo public’s reaction, but also with the clergy’s, in mind. When the tyrant sent Yoftahe to Alexandria with a hand-picked “Patriarch,” it was primarily meant to gain legitimacy in silencing the public and the clergy. When that move turned out to be a farce, he had no choice left but to do the more unconventional demoting process of the Patriarch all on his own.

Third, a “divide and conquer” policy is fully implemented, followed by an active demonization process targeting both the “accused” entity and its supporters (now with official backing), where the foot soldiers pan out among the population to lay the groundwork for the final assault to be taken. Again, all this is done with an eye to the public reaction. If they sense little resistance and much cheerleading, then it is time again to ratchet up the persecution process. This was also a critical step in the case of the Patriarch because initially the overwhelming majority of the population and clergy were on his side. It was then essential for the GoE to exploit an existing fault line to widen a rift between the conservative and liberal wings of the Church. The ironic part is that the government used to support the modernization of the Church until the advent of the crisis. Then it reversed itself to fully support those who resisted change not because it believed in their cause but because they were able to enter a Faustian deal with it. In return for the government’s full support, they would let the Church be used as an extension of the PFDJ apparatus. After correctly sizing up the muted reaction of the clergy and the public, Shaebia put the Patriarch under house arrest, though left at his house and still accessible to few.

And fourth, the despot makes his last move: he goes for the kill and puts those targeted individuals behind bars. Then a public indictment of the accused by Shaebia cadres, in absence of any judiciary process, is set in full motion, officially accusing the arrested with various crimes against the nation in retrospect and vigilantly hunting for anyone who shows the slightest bit of sympathy for the arrested. In the case of the Patriarch, this final process has been recently finalized by officially replacing the Patriarch with one hand-picked by the tyrant and then by forcing his eviction from the traditional home of Patriarchs. And now that they have secluded the Patriarch in a permanent house-arrest, the GoE apparatus has been fully unleashed to stamp out any remaining resistance. At this point in time, nobody knows where the Patriarch is; his seclusion and inaccessibility has become total.

We can clearly see that all along, at every incremental level, the despot has been warily looking at the reaction of the Tewahdo population. A clear indication that the despot does not take major steps without testing the waters is that, in some instances, he has (outrageous as this claim may seem) actually backed away from taking some seriously entertained steps; in some other cases he has reversed himself in implementing a certain policy; and in many instances he has applied his experimentations selectively on population groups that he believed he could easily get away with. An example of the first kind is when he backed away from imposing army conscription on Muslim women. An example of the second kind is when he quietly withdrew most women from the trenches. And an example of the third kind is the notorious parental penalization that has so far been confined to the Tigrigna areas only. Another example of the third kind is the case of clergy conscription in the army, where it is selectively applied on the Tewahdo Church only. Let’s now look at the cases of conscription of women and clergy in the army to understand how Shaebia takes the path of least resistance in all its efforts to subjugate the masses.

(a) Women’s conscription into the army

When the Muslim population in Eritrea courageously stood up against the forced conscription of their women into the army, the tyrant backed down without admitting it officially. The Muslim resistance to such an incursion into their womenfolk was so determined that he quickly realized that he cannot easily get away with it. Except for some few token Muslim women from the urban area, the Muslim population group was exempted from this misguided policy and spared from all the horrendous consequences that such a policy brought about. But this same policy was ruthlessly and indiscriminately applied on the Christian population. Now, don’t get me wrong; this was not because the tyrant loved the Muslims more than the Christians. His reason was much more brutally pragmatic (true to Shaebia’s vulgar pragmatism): he thought if he could apply it selectively on the Christians, he could get away with it, with little protest from the population. We have to remember that Shaebia always takes the path of least resistance (remember the Tigrigna proverb, “HaseKa dembe ab zlemlemelu”). And, time and again, it has been proven right.

A rare case where Shaebia reversed its policy is regarding women in the trenches. The Christian parents began to show their outrage to women conscription into the army only when they saw the extent of sexual abuse that their daughters had undergone under the hands of PFDJ army officials. Only when their daughters came back to the cities and towns deeply traumatized, with tales of horror to tell – sexual coercion, mass rape, unwanted pregnancies, life-threatening abortions, illegitimate children, HIV infection, etc. – did they began to have second thoughts. Many of them were to be stigmatized for the rest of their lives, with little prospect of marriage. Some returned with serious mental problems in a land where there are no viable mental institutions. As a result, outrage among the public was palpable, and the Monster of Asmara sensed it. He quietly withdrew most of the women from the trenches, without ever publicly admitting that the policy has been a total disaster. And now, after tens of thousands of the youth have deserted, thereby threatening the very viability of the army, the tyrant is having second thoughts on this matter. He is quietly introducing the women back into the army. Now that he has totally crashed the determination of the people, he feels emboldened to go ahead with his former experimentation once again, come what may.

(b) Clergy conscription into the army

That Shaebia doesn’t have the slightest bit of respect for the age-old tradition of the people is not only displayed in its forced conscription of women into the army, but also of the clergy. As pointed out above, it would be worthwhile to note that in the 17 centuries of Christianity in the region, not a single ruler has ever attempted to undertake such a sacrilegious act. So Shaebia’s contempt for tradition and religion is, in this case, as clear and as tangible as could be. Yet, the tyrant again shows his pragmatism when applying this demonic policy on the ground. He selectively raids Coptic churches and monasteries to round up the clergy to be sent to Sawa. The reason why Shaebia has so far refrained from doing the same thing to the Catholic Church is, again, simple: the Catholic Church has courageously, and with one voice, stood up against the incursion of the despot in its domain. They even responded to him with a strongly worded letter objecting to his efforts to recruit their clergy into the army. It also helps that the Church has the power, prestige and influence of the Vatican behind it.

In contrast, the Orthodox Church has neither a strong institution of international renown to back it up nor the cohesion among its clergy and its followers necessary in such confrontation. In fact, it was able to withstand the onslaught of the Isayas regime as long as it did through the sheer courage and integrity of one man: Patriarch Antonios. As soon as Shaebia got a foothold in the Church’s domain, it was not hard for this criminal organization to divide the Church and sow discord among its clergy and parishioners. Since the day of the plan’s inception, slowly but meticulously, the tyrant has been inching his way up to the total domination of the Coptic Church. And now, with the final arrest of the Patriarch, his nefarious mission is accomplished.

Now, what we have to ask is this: Why does Shaebia prey on the Tewahdos, among the major religions, disproportionately? What is it about the Tigrignas, in general, and the Tewahdos, in particular, that Shaebia finds it conducive for its social experimentation? There are two characteristics that we need to look at: the confused sense of identity of the Tigrignas and the vulnerability of Tewahdo in face of modernity.

Bypassing their identity

Among all the ethnic groups in Eritrea, the Tigrignas have the most confused sense of identity. They have never developed a sense of being one people. At most, they recognize themselves regionally as Seraye, Hamasien or Akeleguzay, but rarely as Tigrignas. In fact, they have always tried to bypass their Tigrigna identity so as to embrace their Eritrean identity. That means that whatever happens to them in virtue of being Tigrignas will never be admitted, if ever registered in the first place. This confused sense of identity has left them susceptible to the predatory habits of Shaebia; it has found it easy to sow discord among them through division and manipulation.

It is easy to divide the Tigrignas along religious, regional, blood-lineage, generational and even gender lines. It is easy to convince them that what is actually their part as alien to themselves. As a result, they have developed this strange propensity to discover enemies within themselves under the slightest manipulation. It is easy to convince Christian Tigrignas that the Jebertis are alien to them. Conversely, it is easy to convince Jebertis that they have a distinct identity other than the Tigrigna ethnic group. No such division is seen among Bilen or Kunama. It has also been easy for Shaebia to persecute Jehovah Witnesses and Evangelical Christians with such brutality because the Tigrignas don’t see this as happening to parts of themselves, but to identities alien to themselves. Shaebia has also been using regionalism to plant discord among them. The Tigrignas of the three regions keep blaming one another – thus deflecting the blame from Shaebia – while they suffer equally under the brutality of Shaebia. The Warsai-Yikealo divide also has most resonance among this population group; the younger generation’s tendency to blame everything on their older generation is peculiar to this group. Even the brutality that has been happening to their women is hardly perceived as something that is happening to the Tigrigna women; and whenever admitted (which is rare), in their “equalizing” mood, it is seen either as individual instances or as something that is happening to the abstract “Eritrean woman” in general. And when it comes to seeking “purity,” they are the worst of all. They are always in the process of purging the “undesirable” from within themselves, be it “agame”, “Ethiopian” or those who are not “dekebat” – those who are not “genuine Eritreans.” Some of them have even gone as far as to outright deny their “Habesha” identity, in the pathetic attempt that that denial would make them equally “Eritrean” as the other ethnic groups. No other ethnic group displays such abhorrence to its own kind; no other ethnic group displays such suicidal tendency, ironically conducted with so much “patriotic” passion.

This willful estrangement from one's own self reaches its pathological stage among the urban Tewahdos, who are willing to see even their religion as alien to their identity; all for the sake of their newly found ghedli-concocted identity. In their rush to adopt this romanticized, hollow identity, the Tewahdos have been letting Shaebia restructure their religion in a way that fits that very hollowness.

It would have been OK for the Tigrignas to bypass their Tigrigna identity to forge a new “Eritrean identity,” if the latter could have been done without erasing their past, without making a clean break with their culture and without developing an ambivalent relation towards their own kind and their religion. But instead of building up on one’s old self, the polluted ghedli climate demands that one disowns it. This new “Eritrean identity” that has been the concoction of ghedli is a creature at limbo: one is made to give up his old identity with nothing to replace it with. It is nihilism at its best. And the Tigrignas have embraced this hollow identity as no other population group has done. This new “identity” that one comes to acquire as a result of disowning one’s old self is a set of negations, devoid of positive content. Such a creature is marked by uncertainty and will never know what he exactly wants. And that is the whole point; for such a creature will be susceptible to all kinds of manipulations that offer him a new, secure belonging. That is why, to many Tigrignas, “Eritrea” has acquired a quasi-religious status, a belonging immune to verification. That is why whatever evil happens to them, they will never attribute it to their newly found religion, but to the devil inside or outside them.

And among the Tigrignas, the least cohesive and most confused group are the Tewahdos. That, of course, has created a fertile soil to the predatory habits of Shaebia. Consequently, among the major religious groups, Shaebia has found it the easiest to infiltrate, manipulate, divide and eventually conquer. As we have seen above, the demonization, harassment, demotion, house arrest and finally forced eviction of Patriarch Antonios is a good example of how far Isayas has been successful in the all-out assault against the Tewahdo Church with the willful complicity of the Tewahdos themselves.

The urban phenomenon

The Tigrignas’ confused sense of identity didn’t simply come out of nowhere. The fact that the other ethnic groups didn’t fall prey to the predatory culture of ghedli to the extent that the Tigrignas did calls for a different explanation than what all the ethnic groups have experienced under ghedli in common. Even though ghedli contributed a lot to the confused state of identity of the Tigrignas, it was able to do so to the extent it did only because there was already a frayed identity on which to prey upon. If so, what we have to do is to look at the root of this confused identity long before (or separate from) the ghedli phenomenon: the urban phenomenon. Regarding this phenomenon, in one of my comments, I have said this much before:

“The first urban-born generation showed no solidity of character that either their fathers or the Italians had, for both the Habesha and Italian cultures are rich in their own ways. But this generation inherited neither. They had contemptuously put their back on the traditional culture, but at the same time all that they could do was imitate the Western culture. Thus, they found themselves in a cultural void that lacked any certainty. The uncertainty that crept into the major choices they made in their lives created a lethal, nihilist context where everything was allowed. Within such a context, a heroic sacrifice for one’s cause and the massacre of two thousand teghadelti (the case of Falul) are nonchalantly and equally accepted without creating any debilitating contradictions in their mind. It is a world without gravity, where one’s actions are left to float around in a void space with no coordination points.”

Since I intend to look at this urban-phenomenon extensively in another article, here I will confine myself to looking at it as pertaining to the Tewahdo Church only.

Unlike the other religions in Eritrea, the Tewahdo Church has been having a huge crisis in facing modernity; a factor that has handicapped it in the face of a decades-old assault from ghedli. It is the least structured religion and, hence, the least equipped to face the challenges of modernity. Until recently, it has never been able to admit, let alone to come up with a coherent policy, on how to face this challenge. This makes it especially urgent in the case of Tewahdo because most of the urbanization (Asmara) took in its midst.

The Tewahdo Church still remains structured along the archaic, feudal lines that can only be made to meet the spiritual needs of the rural area, if at all. The schooling system, all the way from deacon to debtera, is still a throwback to the feudal times. The priests who have undergone such a traditional education can hardly meet the challenges they face from the urban generation that demands more than symbols in its quest for spirituality. The “rational” aspect of the spirituality that this generation has been seeking is impossible to be met under this archaic condition. That is why the defection rate – to other religions – is highest among the urban Tewahdos. And by the same token, so is this urban generation’s defection to the “ghedli” religion. Part of the tendency of this group to romanticize ghedli comes from the spiritual and cultural void created from the failure of the Tewahdo Church. During the pre-independence era, the certainty that this generation has been desperately looking for were to be met in the ghedli environment only. The fact that many true believers, even now, openly declare that “Shaebianism” or “Eritreanism” is their religion tells it all. It seems that, for long, the urban generation’s spiritual quest has been met by ghedli. But not anymore; hence Shaebia’s hostility towards all the “new” religions that are taking away its “parishioners.”

This is not to say that the followers of other religions, so far as they were urban dwellers, were immune to the appeal of ghedli; it is only that they came out from the ghedli era less affected “spiritually.” For instance, a Muslim who has gone through the acculturation process of ghedli is less likely to be negatively affected as a fellow Muslim. That is to say that, culturally and spiritually, he is better inoculated to resist the ghedli virus than a Christian. For instance, a Christian is more likely to embrace communism whole-heartedly; and worse, more likely to fully immerse himself into the nihilist culture of Shaebia. That is to say, he is more likely to swap his religion for ghedli ideology and his identity for ghedli-concocted identity. And in the case of urban Tewahdos, their “immune system” has been so weakened by a structure-less religion that an attack by a ghedli virus is more likely to be lethal, and its malignant effects to last long.

The reason why Shaebia is antagonistic to all religions is then “religious” in its very nature; as any other monotheistic religion, it cannot tolerate other “competing” faiths. When Shaebia entered Asmara, it was surprised by the relatively large number of young Eritreans immersed in spiritualism – Muslim conservatives, Evangelical Christians, Jehovah Witnesses and Tehadso Tewahdos. It saw a threat to its survival coming from these groups because it rightly felt that they were immune, if not antagonistic, to the acculturation process under Shaebianism. This is the main reason why it set out to destroy them with such ferocity. At the beginning, it felt comfortable with the anarchy and passivity of Tewahdo Church that seemed to allow it whatever it wanted to do. It was only when the Church began to reform in earnest that Shaebia felt the same threat it felt with the others.

At the center of the schism that lies in the Tewahdo Church in Eritrea is how to face the challenges brought about by modernity. There are those in the clergy who are desperately clinging to the past partly because many of them feel they are unequipped to face modernity and, in case of reform, would be left far behind. And then there are those who believe that the challenges of modernity should be met head on by modernizing the Church. That would require, among other things, that the new clergy be educated in a modern ways, that the Tigrigna vernacular be used for preaching purposes, that seeking the youth should be central to the mission of the Church, that the structure of the Church be radically reconfigured, etc. And in doing all of this, the Church was to meet its champion in Patriarch Antonios. The tale of Medhanie Alem Church encapsulates the dilemma in which the Church finds itself in its quest to find its place in this post-modern era.

The Medhanie Alem Church in Asmara was doing all the right things in meeting this challenge. It put highly educated pastors in charge, who not only translated and articulated many of the Church’s teaching in Tigrigna, but also brought a modern structural change within the organization. As a result, it instantly became a magnet to the youth; its Sunday School was attended by more than 3,000 youth. The Patriarch was also planning to build a modern divinity school so as to implement these changes at a more permanent and general level. The Medhanie Alem Church then was a miniscule experiment for what was to happen to the Orthodox Church if everything had gone smooth. No surprise that both the conservative wing of the Church and Shaebia felt threatened by the spectacular success of this experiment. We have seen why the former felt threatened by the Tehadso movement, but we have yet to say why the latter felt threatened too. At the root of Shaebia’s change of heart was the realization that an independent-minded Church, not amenable to its manipulations, was being created right in front of its eyes.

What alarmed Shaebia most was the way the youth were flocking to the Church. In my article, “The Despot Playing It Safe with Patriarch Antonios,” after pointing out that Isaias believed that the Church is “set out to compete with him for the allegiance of the youth,” I went on to state the additional fear of Shaebia, “This was, indeed, too much for Shaebia to swallow, an organization that believes it has a monopoly over the youth of Eritrea. But the despot's fear was not simply that the youth were finding solace in the bosom of the church (rather than in the claws of the PFDJ), but that this spiritualist movement could morph into something bigger that would eventually threaten the very survival of his regime. He knows only too well how many totalitarian nations in Eastern Europe were rocked to their foundations by civil societies that had their roots in religious organizations.” It is understandable then that the regime set out to stamp out the reform in the Church.

Conclusion

From the above, it is easy to see how Shaebia’s religious policy is guided by its most famous maxim of vulgar pragmatism: “Can I get away with it?” When it comes to the minority religions, it set out to totally obliterate them because it believed it can get away with it without any threat whatsoever. First of all, their numbers were too small to be a threat on their own. But central to this decision is also the knowledge that no other Tigrignas will ever stand up for these minority religions. So the realization that the Tigrignas consider these minority groups as alien to themselves (even though almost all of them belong to the Tigrigna ethnic group) was very essential to the regime’s calculation.

When it comes to the major religions, Shaebia’s approach was more cautious. In the Catholic case, it very much realizes that its chance of manipulating the structure of the Church is zero; it would be unthinkable for it to put its own choice of Bishop at the helm. It would also find it very hard, if not impossible, to recruit its clergy for its army. But outside that, the fate of its adherents remains the same as that of Tewahdo adherents – for instance, in the case of women’s conscription into the army. In the Muslim case, the GoE had a hand in picking the Mufti; and it had “disappeared” hundreds of Muslims under the guise of fighting fundamentalism. But when it comes to the kind of deep structural change that has been seen in the Tewahdo Church, Shaebia wouldn’t even dare think of it. And when it comes to its womenfolk, that is a no-no. But when it comes to Tewahdo, there is no bottom line as to how far Shaebia will go in its abuse. And the reason is simple: the Tewahdos are allowing it.

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)