Asmera: the Archeology of Violence Masquerading as Art Deco

“[The Fiat] is the reason I became an architect. It’s a very peculiar building. Structurally it was very bold. Engineers nowadays wouldn’t dare to build a cantilever half the size of that,” says Mesfi Metuasu, a local architect and urban planner who has been working with Asmara’s buildings since 1995. [1]

Asmera: Archeology of Violence Masquerading as Art Deco

Recently, the ruling authorities in Eritrea have submitted to UNESCO a nomination for 4,300 buildings in Asmera’s historic perimeter; the decision is expected in 2017. The authorities have labelled these fascist relics as Asmara Heritage Project. The irony is that, the regime has a history of destroying the indigenous heritage and culture. Likewise, what have been harmlessly called “art deco” buildings journalists and urban historians are in fact an archeology of violence. The article will argue that, an august body like the U.N. should not recognize buildings from the Fascist Italian era as heritage. The buildings represent violence; the buildings aren’t some kind of a giant smiling Buddha. [2]

When the rebel movements conquered Eritrea (1991), they quickly dynamited the modest-sized statue of Ras Alula, the hero who led several battles and defeated the Egyptian army and later the Italians encroaching from the vicinity of the coast of Massawa. The rebels and the public felt little outrage about the act of this cultural violence; the lack of which outrage soon led to a strange request to the United Nation’s Cultural Commission.

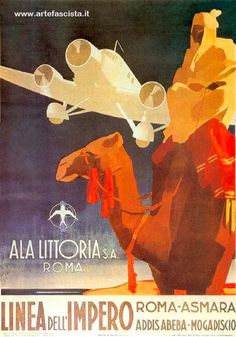

On the back of a plane

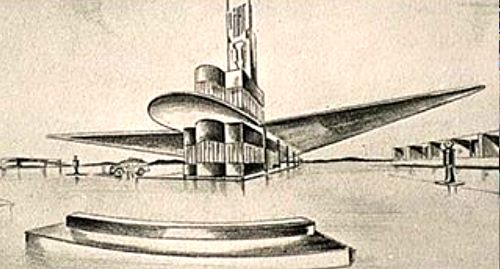

The Eritrean authorities made a concerted campaign for the scores of Fascist-design buildings in the city of Asmera to be recognized as “Cultural Heritages”. Interestingly, many of the structures have the fasces, the symbol of fascist ideology, or something that resembles it. Among these buildings is, the Fiat Tagliero, the soaring image of an Italian plane.

Asmarinos, who religiously love to do the passegiata have certainly seen this structure since their childhood. They grew up however clueless to its symbolic meaning. When they grew up, they left in their thousands to the mountains, their feet shod with the celebrated plastic sandals; whose statue is now located a short distance from the infamous building.

On the back of a camel

They left to “own back” the city, or the “civilization”, which comprises this same building. It took thirty years of protracted war; marching with the low-tech, plastic sandals, or “war on the cheap” to claim back the city from the “meteor”. It took equally many years to discover the real purpose of the soaring plane. The discovery was made; not surprisingly by foreign writers, which says a lot about the cosmopolitanism of the Asmarinos. Yet the structure is still described as a marvelous art deco of the 1920s and 1930s; or of the futurist type.

They left to “own back” the city, or the “civilization”, which comprises this same building. It took thirty years of protracted war; marching with the low-tech, plastic sandals, or “war on the cheap” to claim back the city from the “meteor”. It took equally many years to discover the real purpose of the soaring plane. The discovery was made; not surprisingly by foreign writers, which says a lot about the cosmopolitanism of the Asmarinos. Yet the structure is still described as a marvelous art deco of the 1920s and 1930s; or of the futurist type.

The city has been isolated from the rest of the world. However, the few reporters and travel writers rarely forget to be amazed and smitten by the airplane looking object along with the other Italian constructed buildings. They keep faithful to the drama of the construction; whose architect stubbornly refused to drop the design of large sized wings with nothing to support it. The architect allegedly threatened to shoot himself, we are told. The symbol of the other violence, that is, the representation of modern warfare and horror is put aside to this day. Hiding the mission and the utility of the contraption calms the occasional tourist, the few reporters, and more importantly the public. What was the meaning of this icon, then?

It was after, 1935, the year Ethiopia was invaded by Mussolini using Asmera as rear base to invade Ethiopia. Among the most extraordinary structures designed during this period was the Fiat Tagliero service station constructed in 1938. Located outside the city center at the junction of the two main southbound roads, one leading to the new airport and the other to Ethiopia, the Futuristic form of Fiat Tagliero soars above the road, imitating what was the most explicit symbol of modernity at the time”, stated Edward Denison. [3] What other purposes did the prime location of the Fiat Tagliero hide? What was its real essence behind the theme of architecture?

Architecturally, the most essential characteristics in it is the violence, the racism and the contempt for the races of the continent; particularly the victim nations of Libya, Somalia, Ethiopia and Eritrea. Fascist ideology erected it to indicate the might of modern power of the white race versus the “static” condition of the natives. The icon celebrated the role of the airplane in subjugating the resistance of the people in the “backward and slave-practicing” kingdom of the Ethiopia. The icon was a testimony of the power of industrialized warfare in avenging the defeat of Italy by an African race in at the Battle of Adwa (1896). The icon signified total war, including the indiscriminate use of poison (mustard) gas on soldiers and civilians alike. Yet what would be considered as an eyesore in other places; is cherished and embraced by the Asmarinos, who lately became the rulers.

In South Africa, the statue of Cecil Rhodes, who played a critical role in subjugating the peoples of southern Africa; has lately been the target of demolition. Located in the south of the continent, it faces north towards Cairo, Egypt; the direction of his huge envisaged empire. While the statue of Cecil Rhodes has been the target of anger and protests; the soaring-plane is fenced-off and deteriorating like its other sister buildings. The neglect isn’t from a deliberate policy, but from lack of funds.

The United Nations, which rightly condemns the destruction of historic buildings, such as, the giant statue of Buddha and the ruins of Palmyra, Syria would be ill advised to recognize the Fiat Tagliero and others in Asmera as a Cultural Heritage and allot money for renovation. Withdrawing the recognition is the least expected from an institution that venerates universal values. By doing this, the institution would help restore the true heritage of the people; in contemporary Eritrea and Ethiopia. The true heritage may help address complete identity loss, confusion and despair of the public in Eritrea, whose major obsession now is not the miss-educated architect’s (quoted above), but boarding a plane and soaring north to Europe and the rest of the West.

Notes

[1] The Guardian, Architecture, Inside Eritrea: Africa’s “Little Rome”, the Eritrean city frozen in time by war and secrecy, August 18, 2015.

[2] Mukoya, Thomas; Modernist architecture in Eritrea; Reuters; March 9, 2016.

[3] Denison, Edward; Ren Guan Yu, Eritrea: Refinding Africa’s Modernist Experience.

![[AIM] Asmarino Independent Media](/images/logo/ailogo.png)